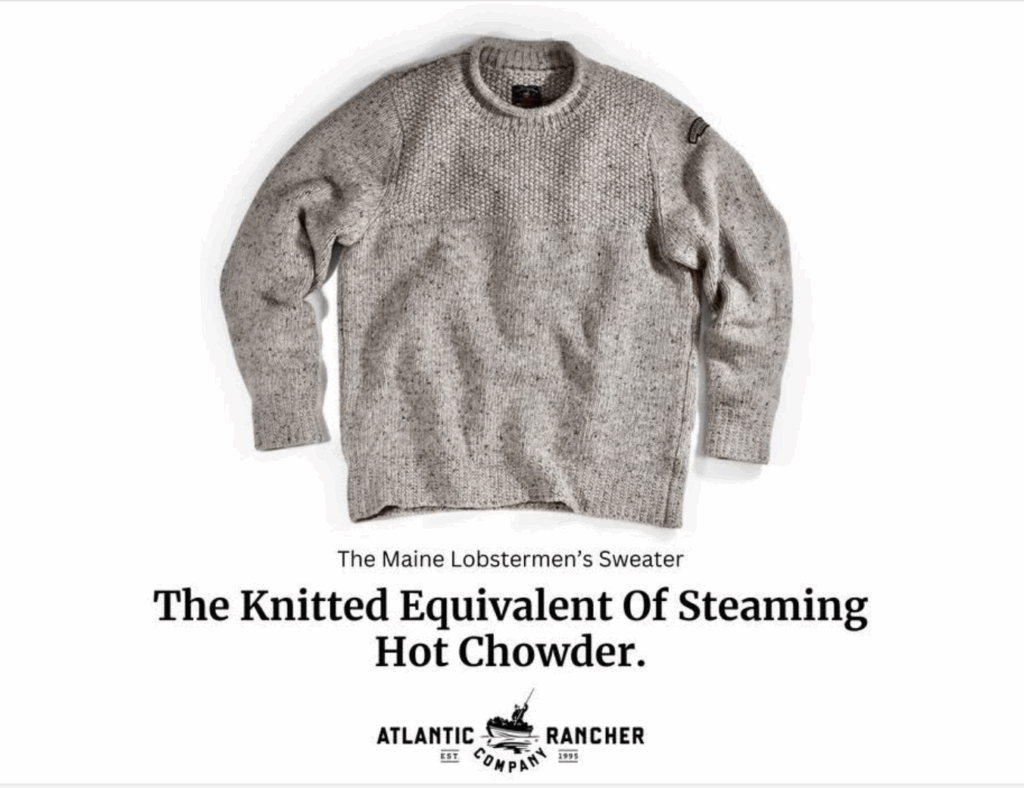

It’s not my kind of sweater. But it’s my kind of ad.

On communication, professional and otherwise.

by David Murray // Leave a Comment

It’s not my kind of sweater. But it’s my kind of ad.

by David Murray // 2 Comments

Yesterday I guest-lectured at a speechwriting class at the University of Florida. I was on Zoom for 25 minutes, telling some things I think I know about rhetoric and speechwriting to young people who I hoped would appreciate hearing.

Soon after I got off the call, I happened to read a pretty chilling piece in The New York Times, about how professors are having to share their course outlines with parents and others to make sure they don’t include words like “diversity,” “equity,” “inclusion” and “culture.” And so on.

“Indoctrination,” is the term conservative critics use to describe what they think college professors are doing to kids, and the reason for all this syllabus surveillance. But these students are 20 years old, not six. If they’re as easily brainwashed as university critics say, then these young jellyfish heads shouldn’t be allowed in front of a television set, or a billboard. In reality, what a university education often does is what I call “undoctrination“: opening cocksure young minds to the notion that they don’t know everything, after all.

None of which was my agenda yesterday, of course. As I was talking to this class, I realized I knew nothing of their backgrounds. I didn’t assume anything, either. I hoped they’d learned a lot in the course I was barging into … and I hoped they’d had a decent grounding in rhetoric in other college classes, and high school before that. (During the discussion, one said she had a friend who writes speeches in the Trump White House. Which only made me wish I had more time—and could appear in person, for discussion.)

In any case, I think I represented myself as what I imagine I am to a college undergrad: A surprisingly still-enthusiastic ancient man who has accumulated many experiences and ideas over the several centuries I have lived.

I assumed the students would assume: Some of these ideas might be useful and correct. Others are going to be old and irrelevant. I assumed the students would know they had to sort that out for themselves. I was, I am, delighted to let them do so, as they will. I am somewhat curious but not quite nosy about what they take to heart and what they reject. And I’m open to but not counting on the idea that I might receive feedback from their professors that will make me more thoughtful and useful (though not necessarily agreeable) to the next group of undergrads.

Anyway, I presented my truth with cheerful abandon—unconcerned about bringing trouble to the two adjuncts who brought me in. They know my act. If they were worried, they wouldn’t have invited me.

But these indoctrination accusations warp everything, and probably make even good teachers question themselves. (Imagine what they do to bad ones.)

My daughter, a senior at a large state university, has told me that her psychology and sociology and social work professors are constantly couching their teachings with phrases like, “I’ll probably get fired for saying this, but ….”

And—even creepier—they’ll express an idea and then add, “Now understand, I’m not telling you you have to believe this.”

That goes without saying, Prof. And it should go without having to.

by David Murray // Leave a Comment

A reader of the thrice-weekly newsletter I write, Executive Communication Report—to which you would be crazy not to subscribe because it is both useful and free—remarked on this item, this morning.

“Geez! Despair, hopelessness, extinction. WTF!”

Brian Jenner is my counterpart in Europe. His views on many things are as different from mine as his personal style. (Re. style: Jenner lives in Bournemouth, England near the Isle of Wight. And he occasionally makes a little promotional music—rapping in the style of white.)

E-MAIL SUBSCRIBERS, VISIT WRITING-BOOTS.COM TO VIEW VIDEO.

But it’s our temperamental divergence that cracks me up—and him too, I’m sure.

When I try to draw people to an event at the Professional Speechwriters Association, I often remember Napoleon, who is said to have said, “A leader is a dealer in hope.”

Despite the demonstrably dark times we seem to be living in, and my own occasional expressions of despair, when I’m trying to lead others, I try to keep on the sunny side of life. It’s I have a dream today, not I had a nightmare last night.

But Jenner? Last year he invited people to the same conference with the headline, “Experience Cultured Europe While It Lasts.” Even in promo mode, he’s more in rhetorical line with his late countryman Winston Churchill, who said in 1940 in England’s darkest hour, “If this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.”

P.S. Jenner’s conference itself is a delight—and in some ways more lighthearted than the one my organization convenes in D.C. As I chronicled after speaking there in 2023. I was the closing keynote, because as Jenner has told me, he always puts “an American” on last, to send people out on a feel-good note.