Won my tennis league last week. This was the first year I played since 2019. Won the league that year too, leading to this grand and uplifting trophy ceremony with the commissioner, himself clearly moved by the moment.

On communication, professional and otherwise.

by David Murray // Leave a Comment

Won my tennis league last week. This was the first year I played since 2019. Won the league that year too, leading to this grand and uplifting trophy ceremony with the commissioner, himself clearly moved by the moment.

by David Murray // 4 Comments

Writing Boots readers know I hate to offer anything useful here, because you’re not supposed to get something for nothing. But every once in awhile I cave in to my sympathetic nature.

Toward the end of a meeting of professional communicators recently I asked how everyone was doing, at work.

“I feel a high level of existential stress,” said one, noting that she has meetings from 7:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m. all day, and “work starts at 5:00 p.m.”

“I feel always at risk of burnout,” said another, and rout was on.

“I’m too busy, and I farm out all the fun stuff. I don’t have the bandwidth to do the interesting stuff.”

“There’s no room for error in this work.”

“I could not take a day off without having to pay for it all weekend long.”

“We make it look so easy and we do it quickly and well—and then people think it’s easy work.”

“How do you manage the fatigue, malaise—and, not to use a bougie word, ennui?”

Someone bashfully, one of the participants asked if we’d thought about something called, “Start, Stop, Continue.”

Maybe one or two had—but the rest of us said, “Go on!”

It’s this simple, she explained:

With your boss, you set aside a moment to write down:

• Here’s what we want to do. (To better serve our organization and its mission.)

• Here’s what we do. (Usually a combination of strategically vital work and “legacy” programs” as they’re politely called in corporate circles.)

• What can we stop doing? (Again, to better serve our organization and its mission—maybe more sustainably, while we’re at it.)

Seems to me like a conversation that ought to take place annually if not quarterly in most corporate working groups.

And if you find that notion insultingly basic on one hand, or embarrassingly unrealistic on the other? Well, then I haven’t broken my rule against being useful after all.

by David Murray // 1 Comment

While writers worry about AI robots replacing us, they’ve already begun rejecting us.

It’s the only way to explain a recent situation where a friend followed a hiring manager’s recommendation to apply for a big speechwriting job. Then a couple days later an email came from the company at 5:00 a.m. precisely, stiffly telling my friend she’d been eliminated from the search because she doesn’t fulfill all the baseline requirements.

How do we know the rejection was AI generated? Real HR people don’t get back to you.

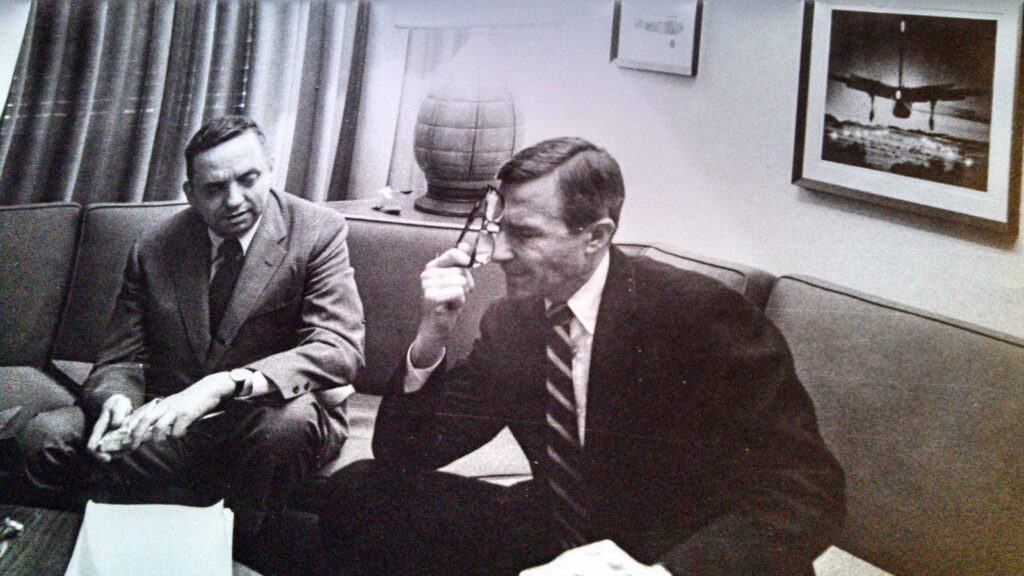

As is becoming the theme of the week, a horrifying glimpse at the present takes me back to the past—to when my dad was trying to hire writers to work at an advertising agency in Detroit, back in the 1960s.

He was willing to talk to anybody to get decent copywriters in there, because the hotshot New York writers wouldn’t go to Detroit, which they saw as, “like two Newarks.”

He fought the agency’s management for the right to see candidates without the personnel department filtering out potentially brilliant creatives “for wearing funny shoes.”

Look, people. Writers are weird. It’s kind of their thing.

Long ago I compiled a little litany of speechwriters I’ve known. In part:

I know a speechwriter/cabaret singer.

I know a speechwriter who operates, for part of his living, a regional association of speechwriters. For the rest of his living, he runs a regional association of funeral directors.

I know a once-closeted gay speechwriter who, when presented with an opportunity to work for a powerful leader who happened to support anti-gay policies, retired.

I know about a speechwriter, Edgar Jung, who wrote a withering anti-Nazi speech, and tricked a German government official into delivering it to an audience of Nazis. (The official survived. The speechwriter was executed.)

I know the speechwriter who was writing for Penn State when the Jerry Sandusky scandal blew up. Asked during a Q&A at a speechwriting conference how she handled that siege year, she said, “Wine and pills.”

I know or have known speechwriters named Tack Cornelius, Cappy Surette, Vinca LaFleur and Lucinda Holdforth.

I know several speechwriters who are working hard to create a speechwriting code of ethics. I know several other speechwriters who think that is the funniest thing they’ve ever heard.

I know at least two dozen speechwriters who have been interviewed and rejected by the same Fortune 100 CEO.

I’ve known more than one speechwriter who was cast aside by a CEO but not fired, and spent miserable, idle years on end waiting for a new boss to come along and use him again. (One did.)

I know a freelance speechwriter whose marketing strategy centers on speaking at conferences. But he hasn’t traveled to a conference for the last three years because his aging and anxiety-ridden dog can’t bear to be without him.

I know a rock band called Speechwriters, LLC.

I know a speechwriter who quit speechwriting after 30 years to be a real estate agent. “I love it and wish I had done it 20 years ago,” she says.

I know a speechwriter who stopped writing speeches and started recording audio books. She misses her speechwriter friends.

I know a speechwriter who once told me on his fifth drink: “You know, when I recall the happiest moments of my life—they’ve all come when I’ve been by myself.”

I know a speechwriter who grew up in a trailer smaller than the corporate jet he now travels on with the CEO he writes for.

And so on.

Sorry, HR propeller heads. If you train your AI mo-chine to eliminate all the weirdos and misfits from your search—good luck finding a speechwriter!