Illinois is promoting a post-COVID return to Illinois tourism with commercials that convert the REO Speedwagon song, “Time for Me to Fly” to “Time for Me to Drive.” I travel Illinois byways on a motorcycle, so for me it’s, “Time for Me to Ride.”

In anticipation of Illinoisans’ road-trip reacquainting, I thought I’d offer this piece, first published here in October 2016—a month before Trump was elected—about a backroads trip I took across rural Illinois. A version of it appears in my book, An Effort to Understand, under the title, “Other Life, Not So Far Away.” —DM

___________________________________________________

A very good writer who grew up in a small town in Illinois and now works as a writer in the city wrote a really thoughtful piece last week about why the people who go for Trump, go for Trump. “I was born and raised in Trump country,” David Wong writes. “My family are Trump people. If I hadn’t moved away and gotten this ridiculous job, I’d be voting for him. I know I would.”

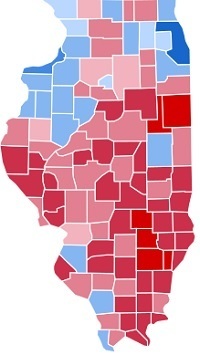

I have just enough authority to praise the piece because I ride my motorcycle on backroads through the rural, red counties in Illinois.

Over Labor Day weekend last year, I took Ogden Avenue out of Chicago and rode it on a southwest diagonal through many of these counties down to the Mississippi River. I recorded a little of what I saw and felt on the way there and back. Reading Wong’s piece, I felt like I was back on Rt. 34—but this time, riding past the hundreds of Trump signs that are surely there now. Excerpts from Wong in italics, excerpts from mine in Roman.

***

As a kid, visiting Chicago was like, well, Katniss visiting the capital. Or like Zoey visiting the city of the future in this ridiculous book. “Their ways are strange.”

And the whole goddamned world revolves around them.

Every TV show is about LA or New York, maybe with some Chicago or Baltimore thrown in. When they did make a show about us, we were jokes—either wide-eyed, naive fluffballs (Parks And Recreation, and before that, Newhart) or filthy murderous mutants (True Detective, and before that, Deliverance). You could feel the arrogance from hundreds of miles away. …

Hey, remember when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans? Kind of weird that a big hurricane hundreds of miles across managed to snipe one specific city and avoid everything else. To watch the news (or the multiple movies and TV shows about it), you’d barely hear about how the storm utterly steamrolled rural Mississippi, killing 238 people and doing an astounding $125 billion in damage.

But who cares about those people, right?

To those ignored, suffering people, Donald Trump is a brick chucked through the window of the elites. “Are you assholes listening now?”

***

Urban sprawl turns into rural road in Oswego—you feel it. And you could probably get a good country breakfast at Plano, Sandwich or Somanauk, but I didn’t take any chances. I waited until I hit Mendota, about 100 miles west.

I had waited long enough. Having been hurtling face-first through the wind for a couple hours, I walked into Ziggies Family Room Restaurant in a zombie state familiar to me, from lots of back-road rides through America and Canada (my Triumph passed 20,000 miles on this trip). I tried to appear as a normal human being despite the intense introversion that two hours of engine meditation creates. Tried to appear as a normal American through the self-protective shell you build to keep Chicago out. Tried not to rub my helmet-itchy scalp while ordering my eggs.

Six old guys sat at the next table over, theorizing about why a tractor axel had broken one day and not another day, talking about a record flathead catch (81 lbs., and the guy threw it back!) and debating with some humor and at great length the proper size of a regulation corn dog, thus to determine what constitutes a “jumbo corn dog,” being advertised on the Ziggies menu.

The waitress finally gave in to her curiosity about the spaced-out drifter at the counter, and she asked me where I’d come from. When I said Chicago, she said her sister had dated a fellow in Chicago once.

“Chicago’s not so bad,” she said, provided you learn a few tricks about city life. For instance, she learned the hard way never to give homeless people money. Because if you give money to one, they’ll gather around you by the dozens.

“Give them toothpaste or soap,” she said. “Anything but money!”

***

The foundation upon which America was undeniably built—family, faith, and hard work—had been deemed unfashionable and small-minded. Those snooty elites up in their ivory tower laughed as they kicked away that foundation, and then wrote 10,000-word thinkpieces blaming the builders for the ensuing collapse. …

Rural jobs used to be based around one big local business—a factory, a coal mine, etc. When it dies, the town dies. Where I grew up, it was an oil refinery closing that did us in. I was raised in the hollowed-out shell of what the town had once been.

You open the classifieds and all of the job listings will be for fast food or convenience stores. The “downtown” is just the corpses of mom and pop stores left shattered in Walmart’s blast crater, the “suburbs” are trailer parks. There are parts of these towns that look post-apocalyptic.

I’m telling you, the hopelessness eats you alive.

***

The next stretch is farm fields punctuated by happy speed reductions into towns so small—Dover, Princeton, Wyanet, Sheffield, Neponset—that when you hit Kewaunee (pop. 12,676), it feels like a metropolis, and you’re glad to back out to the country, and to Galva (pop. 2,758) and then Altona (pop. 531) and Oneida (pop. 700).

I stopped and listened to the Altona Tigers marching band, rehearsing out of their uniforms; they didn’t sound good, but they sounded wonderful. I think it was also in Altona that I took a photo of a Lutheran church sign, “Worrying is like praying for what you don’t want!”

***

The rural folk with the Trump signs in their yards say their way of life is dying, and you smirk and say what they really mean is that blacks and gays are finally getting equal rights and they hate it. But I’m telling you, they say their way of life is dying because their way of life is dying. It’s not their imagination. No movie about the future portrays it as being full of traditional families, hunters, and coal mines. Well, except for Hunger Games, and that was depicted as an apocalypse.

***

On the return trip: the utter stillness of Labor Day in the country. I rode through many towns without seeing a soul; I was looking for a tavern for lunch, but even most of those were closed. I resigned myself to wait until the big city in Kewanee, where they’d just be wrapping up their annual Labor Day Hog Days Festival and some places would have to be open. But then I spotted Mary’s Restaurant, on the eastern outskirts of Galva. There were a few cars outside.

Eight locals and a middle-aged biker couple nursed beers in dim light. The kitchen wasn’t open, so the only food available was chicken soup and chili, simmering in crock pots. Six dollars, all you could eat, out of Styrofoam bowls. And so utterly home-made, passing it up would have been like snubbing your grandmother.

The Cubs played the Cardinals on the TV. It emerged that half the crowd was Cub fans, half Cardinals’. The Cubs were winning, but the Cub fans knew this was the Cardinals’ year, and so did the Cardinals’ fans.

“You must be Mary,” one of the bikers said to the woman behind the bar.

“Who else works on holidays?” Mary asked, rhetorically.

***

So yes, they vote for the guy promising to put things back the way they were, the guy who’d be a wake-up call to the blue islands. They voted for the brick through the window.

It was a vote of desperation.

***

I pulled off to look at the Hennepin Canal. A little later, I rode past a no-trespassing sign, a quarter mile down a narrow path through a soybean field to the base of a wind turbine, for a picture. I rode through the parking lot of a rollicking biker bar in a grain mill near Langley, but didn’t stop for a beer because I wasn’t feeling bold enough to walk alone into a place called Psycho Silo.

In the next town I saw another church sign—someone ought to collect these messages in a coffee table book—that said, “Living without God is like dribbling a football.”

And I rode to the back of a cemetery at Wyanet and lay down in the grass for a nap. Though I was exhausted, unseen insects tickled my arms and neck each time I started to drift off.

***

“But Trump is objectively a piece of shit!” you say. “He insults people, he objectifies women, and cheats whenever possible! And he’s not an everyman; he’s a smarmy, arrogant billionaire!”

You’ve never rooted for somebody like that? Someone powerful who gives your enemies the insults they deserve? Somebody with big fun appetites who screws up just enough to make them relatable? Like Dr. House or Walter White? Or any of the several million renegade cop characters who can break all the rules because they get shit done? Who only get shit done because they don’t care about the rules?

***

I sat at a hundred red lights, burning from above in the 90-degree late-afternoon sun and baking from below by the heat of my own engine, as Rt. 34 turned back into Ogden and a record-long strip mall and then the city and a family of eight sisters almost killed some of themselves running across Cicero and cops ran a red light just because it was the ghetto and I almost crashed my bike trying to get a stupid video shot of the approaching skyline as I emerged from the bridge at Ogden and Western.

It didn’t seem like Labor Day in the city. It didn’t seem like any holiday at all. Who works on holidays? Mary in Galva, insects in Wyanet, and all Chicagoans, just to survive.

What kind of a life is this? It’s a rigorous life, at least. It’s our life, for sure. It’s important to know there is also other life, not so far away—and to see it, as clearly as we can, to the extent we can will ourselves to slow down and look, make eye contact and see, calm down and communicate.

Thanks, David! Good read!