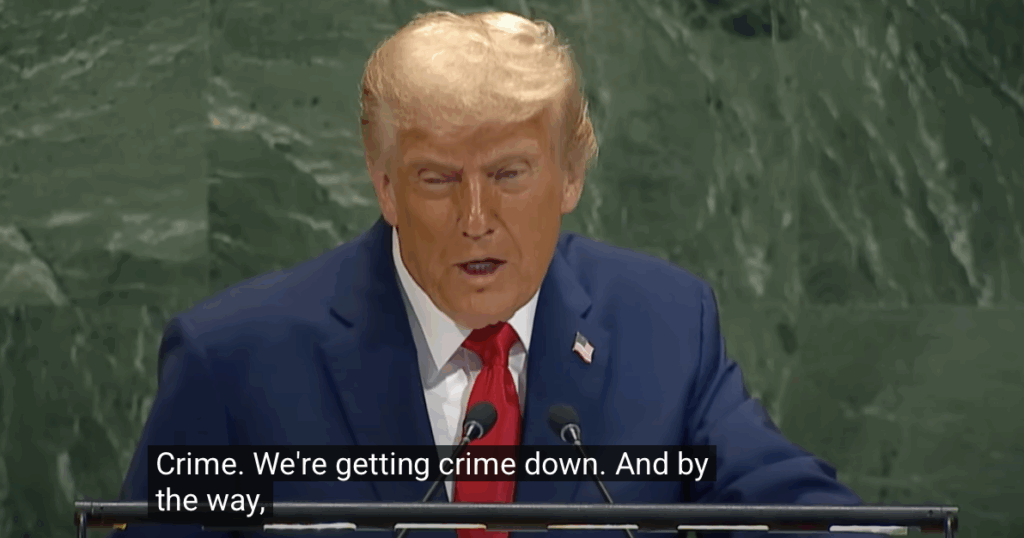

The President of the United States gave a major address last week at the United Nations General Assembly, and we’re not printing it in Vital Speeches of the Day magazine.

Though our archives are not searchable in such a way that I can say this for absolute certain: After 91 years of publishing, I’m pretty sure this is a first.

We’re not refusing to publish the speech because we don’t like it, or the man who delivered it. We have published every one of President Trump’s UNGA speeches heretofore.

And in the 17 years I’ve edited Vital Speeches—a monthly collection of the world’s most important speeches founded in 1934—I’ve included plenty of speeches I loathed, disrespected, found empty, absurd, disingenuous and irresponsible.

In addition to all the wonderful speeches we’ve published over the years, we’ve published many dumb and dangerous speeches by American presidents, foreign leaders, CEOs, nonprofit heads, university presidents, celebrities and even unknown people giving strange addresses in public libraries and at local malls.

We’ve certainly published speeches that supported every theme the president hopscotched across Tuesday: that the United Nations is ineffective and worse, that immigration is a global evil, that climate change is not real.

In fact, my reign as editor of Vital Speeches—and for the last decade its publisher, too—has actually seen a liberalization of the original policy of this oldest continuously printed American magazine, sternly laid down by my predecessors:

The publisher of Vital Speeches of the Day believes that it is indeed vital to the welfare of the nation that important, constructive address by recognized leaders in both the public and private sectors be permanently recorded and disseminated—both to ensure that readers gain a sound knowledge of public questions and to provide models of excellence in contemporary oratory. These speeches represent the best thoughts of the best minds on current national and international issues in the fields of economics, politics, education, sociology, government, criminology, finance, business, taxation, health, law, labor, and more.

It is the policy of the publisher to cover both sides of public questions. Furthermore, because Vital Speeches of the Day was founded on the belief that it is only in the unedited and unexpurgated speech that the view of the speaker is truly communicated to the reader, all speeches are printed in full. … Speeches featured in Vital Speeches of the Day are selected solely on the merit of the speech and the speaker, and do not reflect the personal views, or pre-established relationships of the publisher.

I have unofficially but demonstrably added to that policy that Vital Speeches publishes some speeches purely as documents of oral history—a term popularized after Vital Speeches forged its mission—and also on the pure basis of wanting future scholars, who may search our archives in library databases as today’s scholars do today, to utter the by-then-equivalent term for, “WTF.”

(As I often do, reading speeches in our archives. For a single instance: In January, 1941, University of Chicago President Robert Maynard Hutchins gave a radio address urging the U.S. stay out of the war in Europe because our own democracy wasn’t perfect and we committed human rights violations of our own. “We Americans have hardly begun to understand and practice the ideals that we are urged to force on others,” Hutchins said. “As Hitler made the Jews his scapegoat, so we are making Hitler ours. But Hitler did not spring full-armed from the brow of Satan. He sprang from the materialism and paganism of our times. In the long run we can beat what Hitler stands for only by beating the materialism and paganism that produced him.” WTF?)

But even with the guidance I get from our founders about political neutrality, and the new permissions I have added to our mission, I can’t bring myself to pay to publish Trump’s, 8,200-word, nearly hourlong U.N. speech. Why? Because it’s not a speech. Rather, it’s the oratorical representation of what the Wizard of Oz called the Tin Man: “a clinking, clanking, clattering collection of caliginous junk.”

Former Cuban dictator Fidel Castro was famous for giving hours-long orations—one lasting over seven. He gave a four-and-a-half-hour critique of American imperialism at the United Nations General Assembly in 1960, going a little over the 15-minute time limit for delegates.

Vital Speeches’ publisher didn’t pay to print that oral marathon, either—and not just because it would have taken up half the magazine. Because it too was not a speech, but a fulminating filibuster that obviously regarded the audience as mere stuffage. (Stuffage: “human or animal figures added as subordinate elements to the painting of a landscape.” I remembered this term from my interview years ago with Danish rhetoric scholar Christian Eversbusch, about how Hitler regarded his audiences.)

To Castro, it was irrelevant whether its hearers agreed with it as individual human beings or were emotionally galvanized by it as a community. Their only role was to endure it, en masse, to show the world who was in charge.

Leaders who want to use a speech to truly get an idea or a feeling across to an audience—and the speechwriters who help them—know the watchwords are focus, clarity and brevity.

The only reason to speak as long and meanderingly (not to mention as sloppily and belligerently) as Trump did at the U.N. is as a show of power. I’ll say whatever I feel like, and I’ll sit down when I’m good and goddamned ready.

Fine. But that’s not communication. I’m not paying to print it. And you shouldn’t feel obligated to listen to it, either.