I hadn’t seen this Flip video production since Scout and I made it, a decade ago. Watching it again, I couldn’t stop crying.

Why? my wife wondered.

TO VIEW VIDEO, VISIT WRITING-BOOTS.COM.

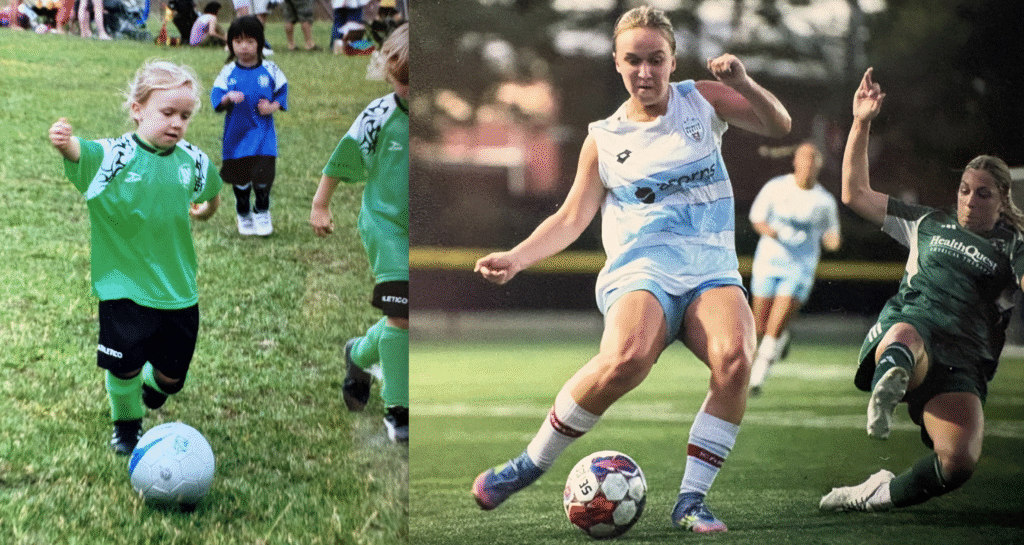

I think it’s because I realized this little drama takes place precisely, almost to the very day of the teetering middle of Scout’s youth.

This single, melodramatic and cornball video captures the beauty of the baby (and the baby’s dorky dad) …

… and the seriousness of the young woman. (And the beginning of the dad’s loss of innocence in the matter of her sports, too.)

Scout’s parents prepared ourselves for the end of her soccer career.

But the middle slipped by undetected—and it came back to hit the old man hard.

Anyway, if you haven’t pre-ordered my book Soccer Dad by now—what does a guy have to do?