Reread Chaim Potok’s wonderful novel The Chosen over holiday break. Hadn’t read it since I was a teenager and have been meaning to for years. I found it just as moving as I had as a lad, and because of its setting in the time of the creation of the State of Israel, twice as topical.

But the book took up another old issue that seems more our meat, here in the communication biz: the wisdom of meaningfully measuring the success of human communication.

In The Chosen, college-student pals Danny and Reuven are talking about the former’s frustrating courses in “experimental psychology.” Danny loves Freud and wants to study the human mind and soul, but his psych professor insists on testing lab rats and dismisses Freud because he doesn’t prove his theories in any quantifiable way. “‘Gentlemen, psychology may be regarded as a science only to the degree to which its hypotheses are subjected to laboratory testing and to subsequent mathematization,'” Danny imitates his professor, exclaiming in outraged retort, “Mathematization yet!”

And “mathematization yet!” is what I think many communication professionals want to scream at bosses who demand numerical “results.” After all ways said bosses hinder communicators from saying anything candid or meaningful or persuasive in an institutional environment—now they want the communicators to devote time they don’t have to employ skills they don’t posses, to count the uncountable and somehow “prove” their communication has worked.

Executive communication professionals, more than their colleagues in employee communications or media relations or social media, have resisted these calls for communication calculus—and gotten away with it for the most part, largely because the leaders they serve are not inclined to doubt the value of their own communication, after all. So executive communication pros generally judge the quality of their work based on the satisfaction of their powerful customers.

The corporate communication measurement pioneer Angela Sinickas—whose landmark manual on communication measurement I edited, way back in 1994—once told me she was once judging a speechwriting category, in a prestigious communication awards program. Candidates had to include an element of quantitative measurement with their entry. One entrant wrote, “After the speech, the CEO gave me a dozen roses (12).”

A number of years ago, an executive communication consultant created a kind of computer program that would analyze the effectiveness of a recorded speech on 31 different criteria of content and delivery. It was sophisticated. It was cutting edge. It was exciting, to a certain type of mind. It sold like a space heater in hell. Why? Because who, in the wake of a speech that likely garnered a politely rousing ovation, would want to find out that, analytically speaking, the talk had not in fact gone over as well as it seemed. The only person less eager to learn that than the speaker, would be the speechwriter.

Like Danny in The Chosen, I am interested in bigger things than can be measured. How would one go about measuring the leadership communication effectiveness of a Winston Churchill, a Steve Jobs, a Greta Thunberg, a Christine Lagarde—an Elon Musk! By the ratings of radio broadcasts, YouTube views, LinkedIn Likes, the length of time employees linger on virtual town halls?

Alas, we sometimes need to argue for a budget. Are forced to justify a big staff in hard times. Are trying for something big, and are asked, “So what?” As an exec comms pro in this position said recently, “Executive satisfaction is everything. Until we need more …”

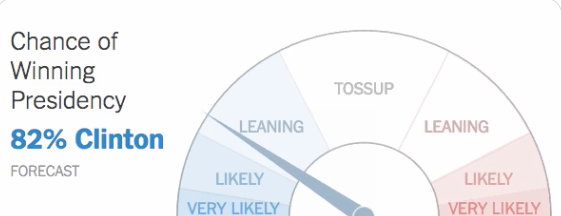

In fact, my organization gathering some of the better minds in exec comms to discuss that subject soon. We’ll let you know what comes out of it. But I will go into it unrepentantly skeptical of sustainable, meaningful quantification of things as complicated and multidimensional as executive communication. I trust it about as much as this falsely reassuring thing, from November, 2016:

Meanwhile, reader: Consider this an invitation not to just tell me I’m wrong about measuring leadership communication, but to prove it, by sending me your own example, either in the comments here or via email, at david.murray at prorhetoric dot com.

If you do so, I promise to eat my hat (1).

David,

There’s nothing wrong with roses but they don’t quantify much. My 2021 book on this topic, entitled “PR Technology, Data and Insights” provides practical advice along with many case studies from companies you’ll recognize. I’ll send you a copy of you send your info to me at mark.f.weiner@outlook.com. Thanks for raising these important points!

Mark Weiner

You bet, Mark. Sending you a note.

If communications can’t be measured, I’ve wasted the past 35 years of my of my life. You can measure anything, assuming you have a clear measurable objective to measure against.

Thanks for writing, Katie. You’ll remember I had you come and speak at the PSA’s Speechwriting School, and also at our World Conference a number of years ago. As I recall, our folks were fairly unmoved.

From your career (which I know has not been a waste—Katie is up there with Sinickas as a comms measurement pioneer, y’all), can you share a particularly compelling example of how you measured *executive communication* specifically, and how it changed the way a leader went about communicating?

I wrote this piece as a provocative fishing expedition, for just such examples.

HEAR HEAR !

I went from political speechwriting–where my salary wasn’t high enough to demand quantification–to corporate speechwriting, where nobody cared about the numbers I picked, just as long as I was making “quarterly progress against my goals.” Nobody cared about the goals, or the metrics, as long as I wrote them down somewhere, and as long as I made progress. 14% greater engagement one quarter … 17% the next quarter … impressions(!), engagement(!), most visited blog post in Slack history(!) BLAH BLAH … boom, promotion.