Last week, I wrote a piece on “A Day in the Rigorously Meaningless Life of One Corporate CEO“: About the CEO of P.F. Chang’s restaurant chain, who gets up at 4:30 every morning and cranks on senselessly, deep into every evening.

The piece earned me mash notes from some, but a LinkedIn connection of mine objected. “Pretty sure [the CEO] gets to decide what is meaningful to him and not you. This was really snarky.”

I replied that “my objection is not to his lifestyle itself … but to the example he sets for employees and others who read about this kind of fanatical life. This kind of stuff sends so many bad messages to normal human beings who would like to succeed without giving every waking hour to their job, I can’t even count them all. You don’t see that? I’m not snarky about these kinds of profiles, I’m enraged by them.”

But of course you have to be the change you want to see in the world, amiright?

So I thought I’d share a day in the life of the CEO of Pro Rhetoric, LLC. (That’s me.)

7:00 a.m. Get up, try to resist watching even five minutes of “The Morning Joe,” because it’s a bad way to start the day. Make coffee, let dog out, feed him, let him out again because he always rushes the first time and if I don’t let him out a second time he’ll poop in the house.

7:15 Put a “cozy fireplace” video on YouTube on the big TV downstairs, and settle with coffee into the old armchair, to research and write the Executive Communication Report newsletter (to which you should subscribe because it is useful and free).

8:30 Turn in ECR copy to my colleague Mike King, who lays it out for my review and approval for 9:00 a.m. release.

9:00 Push out to social media the morning’s post on Writing Boots (to which you should subscribe because it is entertaining and free). Head upstairs to office for the real morning’s work.

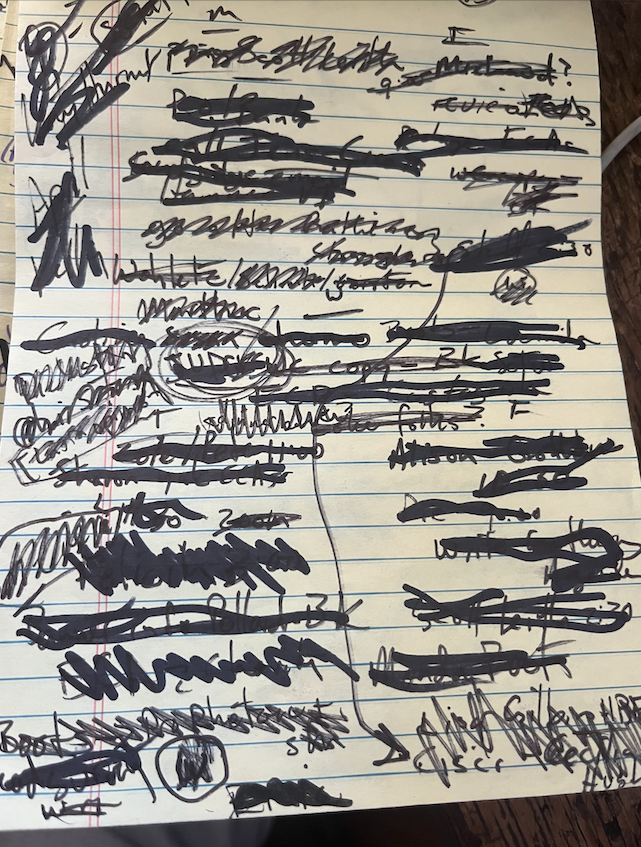

9:30 Attack the to-do list, take calls, make calls. (Below is the to-do list, which gets absolutely completed every single week. If you look closely in this mess you can see M, T, W, T, F. Items on the list range in arduousness from, “call Larry” to “plan World Conference.” But that’s it. That’s the whole system. Has been since I went freelance, in 2000. Never missed a deadline in all that time.)

11:00 Four-mile run. Same route every day.

12:00 Lunch. Turkey sandwich, every day. Dog gets one slice, every day. While I sing him a song titled, “Turkey Time” even though he is stone deaf.

12:30 Twenty-minute nap, dozing off to the New York Times podcast “The Daily.” (I like to learn while I sleep.) My colleagues know that I nap every day, but I never tell them exactly when, because I have a feeling that working while picturing the boss drooling into a pillow is bad for morale.

1:00 After that “spa time,” as I call it privately, I’m back at the desk, really refreshed, to get back in the river of calls and emails and writing and editing in the afternoon.

5:00 Miller Time. Occasionally, I will fool with the next day’s Boots post in the evening, because though it’s not good to drink while you’re writing, it’s often fun to write while you’re drinking. (And edit, too, as I am right now!) But I never (ever) do actual “work” work in the evenings. “Speechwriting,” my colleagues and I remind one another frequently, “is not an emergency.”

In that amount of time—along with three formal, weeklong all-company “recesses” during the year and the usual number of random days or afternoons off, I manage to lead a company that employs three people full time and pays a couple dozen vendors on the regular and serves thousands of customers and other partners, hundreds of whom I know personally and dozens of whom I know deeply. I write my daily blog, edit a twice-monthly magazine and maintain two professional websites. I plan two major annual conferences and market a couple dozen seminars. And I oversee any number of other activities, including two awards programs. And every once in awhile, a book comes out.

Like—that’s enough stuff!

The benefits of my not working more than that include:

• Not being tempted to send emails to the people I work with late at night or on Saturday mornings, which prevents them from thinking or feeling that I think they’re slacking by not working constantly.

• As rich a social life as I want—richer, in fact!

• And baseball on Sunday mornings, and brunch after, with The New York Times.

The downsides of my not working more than that include:

• None.

Of course, it doesn’t matter one bit how much I work, or how little, until I start going around telling people they ought to work that amount, too. Or making them feel, through a piece like this, as if they’re working too much, or not enough, or not in the proper way.

Well, I’ve been working like this since I began to work for myself, almost 25 years ago. So I know it’s sustainable for me and for my family. And I imagine, depending on your circumstances and your line of work (and on how much you like that work), it could be sustainable for you. Though not for my Chicago schoolteacher wife, to whom “it looks so boring!” And of course, I couldn’t do her job for one morning.

In any case: Now I ask Mr. Four-Thirty to Nine: How many other people could sustain your lifestyle for more than a month straight? And why in God’s name would they try?

Yes, it’s fine if you want to live like a crazy person. But keep it to yourself. And I mean, closely.

Daytime “spa time” is most underrated!

Indeed, Diana!