The New York Times was all excited yesterday that today’s Kansas City Chiefs-Dallas Cowboys game could be the most-watched regular-season NFL contest ever.

“It’s the perfect confluence of three of the biggest brands in American culture—the Cowboys, the Chiefs and Thanksgiving,” the article quoted CBS announcer Jim Nantz ejaculating.

Well, I’m watching a different Chiefs-Cowboys game—one played 50 years ago this month—not on Thanksgiving, and during a time when football clubs weren’t called “brands” and football wasn’t considered “culture.”

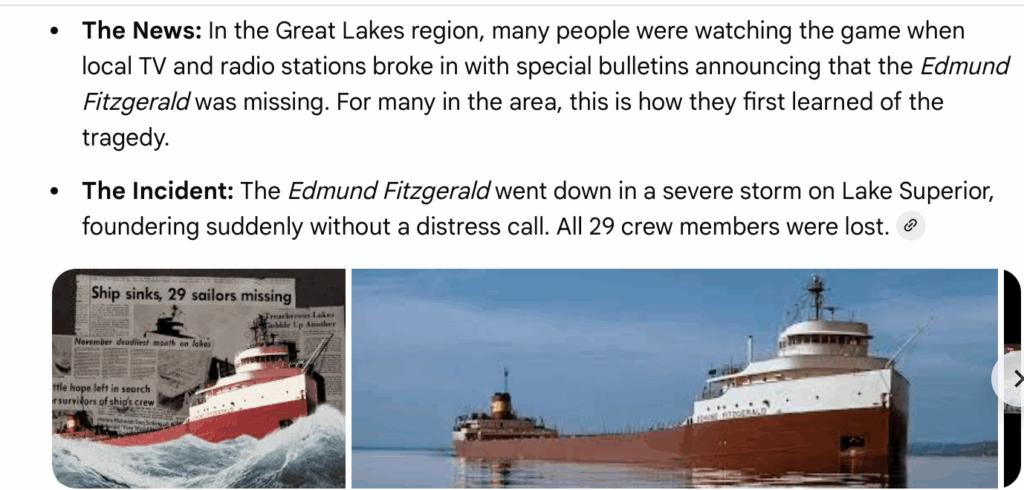

I’m watching the Chiefs-Cowboys Monday Night Football game from November 10, 1975—the night the Edmund Fitzgerald sank, in another perfect confluence: the confluence of a storm system from the southwest meeting the Alberta clipper on Lake Superior at just the wrong time.

By kickoff, in fact, the great freighter had already gone down—probably about 40 minutes before, in fact. I hope ABC announcer Howard Cosell didn’t know it as he showed off his dumb cowboy boots introducing the game in the press box, saying in his strange New York accent, “These boots are made for walking. And that’s what they’re gonna do. Right here in Dallas, Texas. While we’re all here with you.”

I’m currently reading John U. Bacon’s new book, The Gales of November: The Untold History of the Edmund Fitzgerald. When the call went out that the Edmond Fitzgerald was missing, the crew of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Woodrush was enjoying a rare full day off in Duluth, Minnesota, and an even rarer sailor’s chance to watch Monday Night Football. They’d laid in Old Milwaukee and pizza. They saw a local-TV scroll on the bottom of the screen: “All crew members of the USCG Woodrush to report to the ship.” They got a call confirming the order, and only when they got to the Woodrush did they realize they were headed across Lake Superior on a dangerous and ultimately hopeless rescue mission.

But let’s get back to the broadcast. After the opening set-up, a commercial for Zenith television sets: “The American worker. Some people have forgotten the craftsmanship he brings to his job. Some say he’s not as important as he used to be. Well to that, we politely answer, ‘Bunk.’ … American workers—Zenith workers—they make sure the quality goes in before the name goes on.”

I’ve written here—maybe boringly, maybe obnoxiously—about how I came to respect-to-the-point-of-idolizing “the American worker,” based on some American workers I’ve known. And why this country is fucked if we don’t find ways to remember to do the same—a half century after some advertising copywriters for Zenith tried to remind us. Maybe some of us have needed reminding about the contributions of the rest of us, all along.

(Not that I’m overly sentimental about it. Just last weekend in Cleveland I got stuck at a bar with a veteran ocean sailor who tried to tell me that no writer is to be trusted to write about sailing. After explaining to him how I’ve sailed down the North Atlantic and down the Baja Peninsula and up Lake Michigan to Mackinac and written about it, he insisted that only a true sailor could capture the experience. Meaning, I finally ascertained to my disbelief, a non-writer. “You,” I heard myself furiously, joyfully, yelling into his thickly waxed ear, “are a fucking idiot!”)

End of the first quarter. Kansas City leads 3-0. By now, the greatest of the Great Lakes freighters has been lost in the Great Lakes “Storm of the Century” for about 90 minutes. Though ABC affiliates have been running announcements across the bottom of their screens in the Upper Midwest for some time, no word of it on the national broadcast. Five years later, Cosell would interrupt Monday Night Football to announce the death of John Lennon. Will he note the death of 29 crew members of the Edmond Fitgerald? The terrible night is young.

(I, too, was oblivious to current events in 1975. Here’s me on the bike I got for my sixth birthday, April 30—the day Saigon fell.)

A commercial is on, for Homelite chainsaws: “For the pro and the man who wants to cut like one.” When was the last time you saw a chainsaw commercial on Monday Night Football? And now an Old Spice deodorant commercial actually set in a ship’s engine room: “It gets pretty hot down here.”

Cowboys lead 10-3, Chiefs come back to tie it up. Cowboys regain the lead, 17-10 with a great catch by receiver Golden Richards. Jim Nantz can only hope for such action this afternoon.

Meanwhile, crews on a half dozen ships are desperately, desolately searching for the Edmond Fitzgerald, which has lain beneath 25, 30, 40 and occasionally 50-foot waves in the pitch-black Lake Superior night for more than two hours. Maybe the boys will mention this at halftime. “Interesting halftime coming up,” Gifford begins to say. But he doesn’t finish the point, as Kansas City scores again, to tie the game at 17. And then—Great Scott, a turnover on the kickoff!—Kansas City takes the lead 24-17 on a short rumble by Ed Podolak, who sounds like he should be an oiler on the Edmund Fitzgerald.

From Google AI:

And yet, at halftime: Gifford delivers a brief history of the NFL’s “Punt, Pass and Kick” program and announces as a bunch of dopey kids trying to pass the ball as far as they can. (It’s not very far.) Then highlights of the previous Sunday’s games. Then commercials for Bic lighters and Boeing airliners. Then a recognition of several great Texas pro football players, sponsored by Seven-Eleven. ABC’s then-vaunted news organization clearly knew about the Edmond Fitzgerald by now. So must the Monday Night Football announcers. Why didn’t they? How could they not have? Mentioned this?

Look, it’s a big country, and we can only see so much from our pinhole points of view, can only feel so much about public events, amid our own choppy and disorganized inner great lakes. I wrote a book called, An Effort to Understand. I might have titled it more elementally, An Effort to Pay Attention. Forgotten people—Americans, anyway—get really mad and then really loud and eventually, really violent. Especially after they feel they’ve been forgotten, like some people have, for two generations or more, by “the biggest brands in American culture.”

The Cowboys tie the game at 24, soon after halftime. Then the Chiefs retake the lead with a field goal, 27-24. Then the Cowboys go up 31-27. Chiefs now, 34-31. Oh, who gives a fuck? And who will give a fuck later today? More than 40 million Americans, according to The New York Times. “And all that remains is the faces and the names of the wives and the sons and the daughters.”

My little company gathers for an annual meeting. At that meeting, when I remember, I try to explicitly honor the work that each of us does that most of the rest of us forget that we do, or who never realized we do it in the first place. Some of us do more of that sort of work than others, I add. And I name the colleagues who I think those are. And I ask us all to express gratitude for them, for that.

And I guess that’s what I’m asking today. And what I’m doing, the best I can.

Happy Thanks Giving.