I couldn’t accept defeat, I guess.

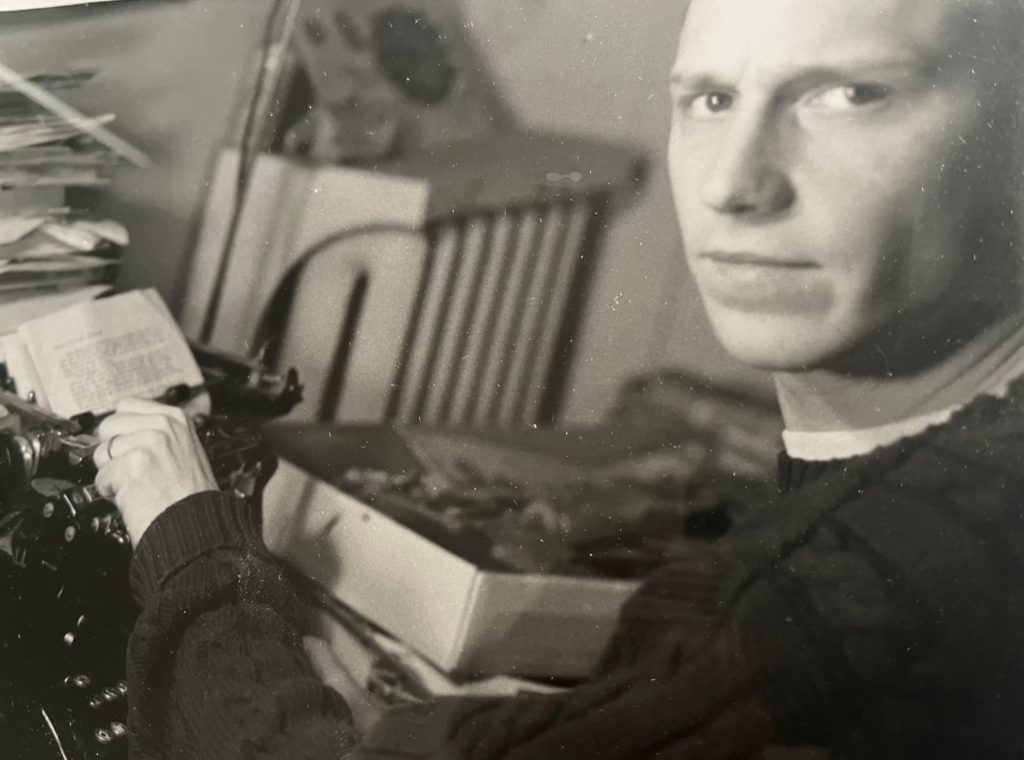

I stayed around another year, taking one thankless editorial job after another—on top of another, actually. At one point, I was writing a monthly magazine all by myself, and most of the weekly flagship newsletter. In fact I was reporting and writing all of that weekly newsletter, except for the industry-influential opinion column that appeared on the front page—the one true plum assignment at this company—which was still being written by the Rival Editor. Who was now my boss.

I was still making about $17,000.

Like a dog that has eaten the same batch of vomit three times, I finally looked elsewhere. I accepted a job at a little PR agency in Colorado—I had family out there—for no more money, but with faith in a new start.

When the President learned I was leaving, he seemed shocked, which shocked me. Even more shocked, shockingly enough, was his father, the Founder. Apparently the old man had slowly, and quietly, come to regard me as an asset to the company. The President confessed to me he had been bawled out by his father, who asked him, “How could you have let this happen?” He made me a counter offer: to cut my workload in half—eliminating the monthly magazine from my responsibilities—and give me complete editorial control of the flagship publication. And he doubled my salary, to the astronomical-sounding figure of $35,000.

A triumph, that was followed by several more over the next few years, as the President brought in a new Manager, who appreciated my talents and promoted me to Editorial Director before I was 30 years old. At some point in there, I got a letter from my father, telling me how proud he was, of my stick-to-it-iveness and my abilities. I’ve still got that in drawer somewhere.

I would go on to leave that organization for a thousand other adventures in journalism and business, but the unbelievable amount of reality that I witnessed there and insight that I gained there during those wild and terrible years would help me in everything else I ever did. Meanwhile, most of my rich life in Chicago can be traced to people I met at that company, or people those people introduced me to.

We were all young together, we were all dumb together, we were all desperate together.

We fucked each other over, and saw how that felt. We supported each other, and saw how that felt. We talked about each other behind our backs, and said things to each other’s faces. We excluded some people from happy hour, and invited everyone to happy hour. We stood up for each other against management, sometimes. We stood up for ourselves, sometimes. We learned what shit we would and would not eat. We saw Martin Luther King Day become a company holiday before many companies recognized it, when the only two Black employees (they were literally sisters), walked into the President’s office and loudly made the suggestion. “Okay!” we heard the President say.

When the Founder was dying of ALS, some of us carried him up to his office and others of us (often the Black sisters) brought him soup for lunch and made sure he was warm. And when the Founder died, some of us slept at the office two nights, working on a memorial issue of the flagship newsletter, and afterwards, the President handed us a note quoting Shakespeare: “Those friends thou hast, and their adoption tried, Grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel.”

***

Unless I’ve got a detail or two wrong in this ancient story, the only objection I can imagine from any of my colleagues from those days would be this: That where we worked was unique, that “DickheadGate” could only happen at a place like that, that we were the original Land of the Misfit Toys. That what we learned together has limited application beyond that particular madhouse.

And of course the place was unique, and knowing that was surely one of the reasons I saw it through. (Another reason was the primary subject matter, in which I had a real interest, which carried me through my career.) And the pain was frequently relieved by the variety of daily madness: The accountant who didn’t feel like entering the subscriber data, so she threw the checks away. Mailman Ron, who daily walked into the open office greeting all the men and women by shouting, “Ladies!” The time a bunch of editors worked late, made our deadline and then got hilariously stoned, Breakfast Club-style, in the Founder’s corner office. The veteran employee who refused to participate in the new Manager’s performance reviews at the cost of a raise because, he thundered, “I will never give you the satisfaction of an accurate measure of my laziness and incompetence!”

And even the colleague who finally, privately confessed, years later, to having written, “David Murray is a dickhead.” That secret is safe with me.

All that said, I don’t think strangers who read this piece will dwell on the difference between my first workplace and theirs; I think they’ll remember their own nasty surprises and humiliations and follies and travesties and triumphs, and the wounds they accidentally inflicted and received as they thrashed around trying to become themselves, trying to find a stable foothold in a shockingly strange work world that had gotten along just fine without them, since the beginning of time.

Which brings us back to that Sunday New York Times piece, about how young people don’t know what they’re missing, as they try to learn the corporate ropes in their living rooms.

I think they’re missing just about everything they’ll ever need to know about their work and their relationship to it—and their workmates, and their relationship to them.

But then, maybe just I take this work stuff a little too seriously. And maybe that’s been my problem all along.

Leave a Reply