I’m sure there’s scientific validity to this notion that a child’s brains aren’t “fully developed” until 25; but I don’t need any science to explain why kids think and act dangerously.

When you’re a teenager, you think of your mid-twenties as a pinnacle, because you simply can’t imagine yourself any older than that. So you think a young artistic death is romantic—a fiery comet, and all that—and a relief, as it gets you out of ever having to become your parents.

And then when you’re 27, you think 27 is old. I remember, at 27, thinking a 31-year-old in my editorial bullpen was pretty much washed up. I mean, at that point, what was really left?

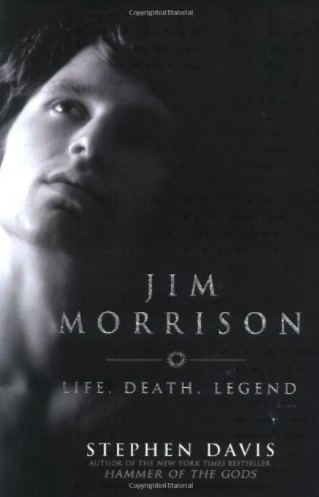

I’ve been thinking about that, listening to the fine 2001 biography, Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend. He felt pretty old at 27, pronouncing himself extinct as a rock star. “Each generation wants new symbols, new people, new names,” the fat, bearded, doomed Morrison told an interviewer resignedly in the last year of his life. “They want to divorce themselves from their predecessors.”

I think I’m revisiting all this (again) in order to get back into the mind of myself, when I was around my daughter’s age.

And I find that adolescent self is still very much alive, still morbidly fascinated with Morrison’s life. But the man almost twice the age Morrison was when he died is pretty well disgusted with the idiocy of that life, too.

And also, with whatever idiocy of that life that can be found in my own.

Whatever arrested development from too much drinking and blabbing, and not enough reading and not enough sober hard work. Every calorie burned on “cool.” And, worst of all, for a writer, any and all literary posing, and self-conscious style. Words, dressed up in black leather pants.

It’s not that I believe Morrison was writing nonsense, or even that he was as pretentious as he is often accused of being. (Though this biography claims that one of the most famous lyrics came when the owner of the Whisky-a-Go-Go told the manager, “When the music’s over, turn out the lights.”)

No, like many young poets, Morrison was writing an intelligent stream of consciousness, creating spontaneous, obscure, seemingly opaque and even subconscious connections between words, writing things he only partly understood himself … and hoping a young writer’s hope that those words and their rhythms would somehow be understood by others—because, as Morrison put it, there’s a “universal mind.”

There isn’t. (Have you noticed?) And as far as hoping your images and loose associations will communicate with another mind, let alone thousands of them—we’re stuck with boring old E.B. White, who wrote in Elements of Style: “When you say something, make sure you have said it. The chances of your having said it are only fair.”

In the end, I don’t think Morrison said very much worth discussing, with his lyrics alone. (Who among us did, at his age?) Anyway, I don’t have anything more in common philosophically or spiritually with another grown-up adolescent Doors fan than memories of our adolescent fascination itself, and all the trivia we feverishly collected back then.

And the music, which still comes for me, and then goes. And then comes back again.

And takes me back, as reliably as anything, to myself, before I became myself.

Which is useful, when keeping largely helpless vigil—as wisely as you possibly can—on your own child, as she tries to do exactly the same thing.

Strange days.

Leave a Reply