You’d yawn, if you started reading here about the trouble with corporate life these days, and corporate communication and I was saying stuff like: “Employee levels of distrust have probably never been higher in North America and … many of our communications fall far short of building understanding, or improving quality performance, or meeting employee needs or management objectives, let alone changing behaviors …”

Tell us something we don’t know, Murray.

Okay, what if I told you those were some of the operative words of a “Communicator Manifesto,” delivered in a speech in the mid-1990s, and published in a Journal of Employee Communication Management that I helped found—that itself is now 15 years extinct. Good God almighty, how am I even still alive?

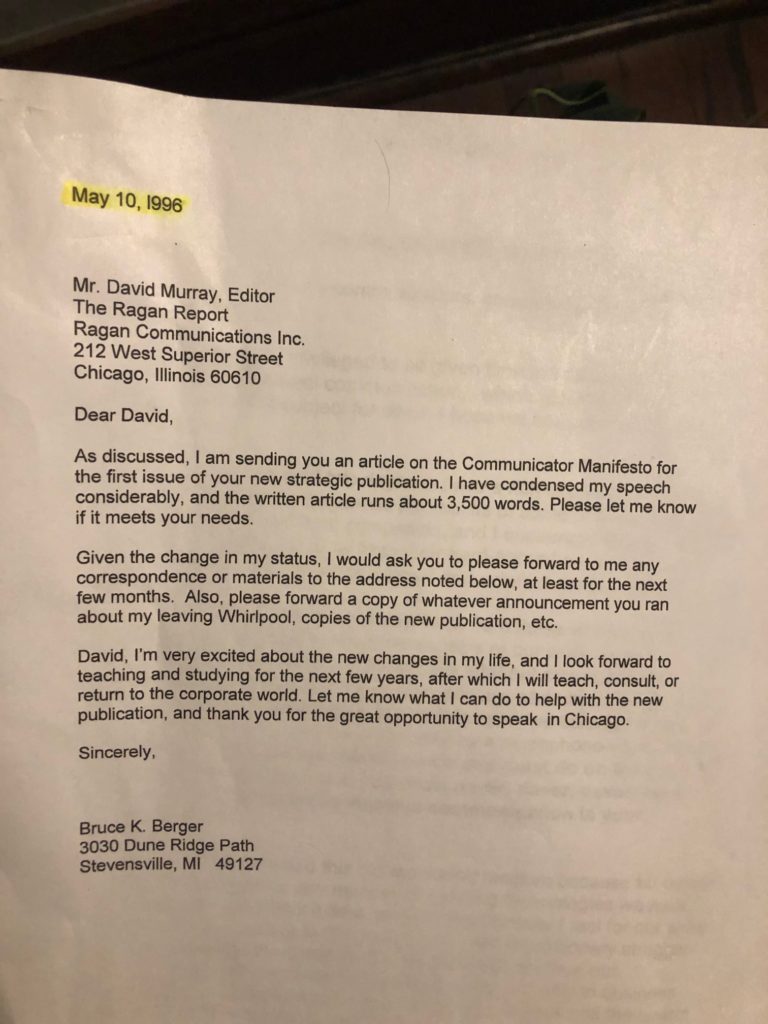

The Manifesto was written not by me but by a frustrated vice president of corporate affairs at Whirlpool Corporation, Bruce Berger, who was departing for what would become a happy quarter-century second act, teaching advertising and public relations at the University of Alabama.

I don’t want to reduce Berger’s Manifesto to Sisyphus’ annual contract—and I don’t want to discourage today’s communicators by sighing, “It was ever thus.”

Rereading this piece after Berger and I reconnected recently, I was also struck by some of what was different, back in the mid-1990s:

American employees at that time were freshly shocked by a huge raft of layoffs—then called “rightsizings”—that had just WillSmithed many of them out of the assumption that they might work at a single company their whole career, as their fathers had done. Globalism still seemed new, brutal concepts like “zero-defect” and “reengineering” were scaring the shit out of people. Dagwood gave way to Dilbert, and the business press lionized asshole CEOs like Jack Welche, and —believe it or not, kids—a guy named “Chainsaw” Al Dunlap.

Cold institutional corporate-speak was a bigger problem then than it is now, at least judging by Berger’s enraged exhortations that communicators fight it “by posting and highlighting atrocious examples on bulletin boards. By sending dozens of photocopies of the offending language to the President and the CEO. By daring to leave such words out of announcements. By embedding the word Companyspeak into your organization’s vocabulary. By making this dangerous and empty language as transparent and visible as we possibly can.”

Alas, much of this 26-year-old piece is painfully and drainingly familiar, including Berger’s call for a communicator’s revolution:

We blow up the old mental model.

We make visible the trust issue.

We give CompanySpeak a dirty name and fight hard to eradicate it.

We challenge all who inhibit the flow of information, ideas, opinions …

We strengthen our own skills and add new ones to the mix.

We develop and own a communication process …

We understand the politics of strategic planning.

We learn how to win.

We fight like hell.

And we never, never, never, never give up.

Nineteen ninety fucking six.

Rather than berate ourselves or our lesser God for failing to solve these stubborn problems in corporate life, communicators might do well to imagine how bad things would have become had stubborn communication humanists like Bruce Berger and his proteges not been on that wall through the next 25 years: The dot com collapse, and 9/11. The advent of social media in corporate communication. The economic meltdown of 2008. The Trump election. COVID, the George Floyd Summer and January 6. How alienated would corporate workers be if some culturally literate humanists in corporate communication departments (and elsewhere throughout the corporation, wherever they found themselves working) weren’t fighting beancounters and propeller-headed bureaucrats with all the guile and courage and energy they could bring to bear?

I will run this piece by Berger and hope he responds. But my feeling is that corporate management does listen more and bullshit less than it did back in Berger’s day. That corporations are somewhat less Kafka-esque, Heller-esque and Orwellian places to work and more responsive to employees’ demands. And that more managers, all the way up to the CEO in some cases, would embrace Bruce Berger’s definition of the meaning of corporate work:

We would like to find the most effective … most productive … most rewarding way of working together. We would like a work process and a set of relationships that meet our personal needs, too … our personal needs for belonging … for contributing … for doing meaningful work … for the opportunity to make a commitment … for the opportunity to grow and to be at least reasonably in control of our own destinies. And then, from time to time, we’d like someone to say, “THANK YOU.”

Well, as the comic Stephen Wright used to say right around that same time: “You can’t have everything. Where would you put it?”

Bruce Berger—and everyone else who remembers what it was like to work and communicate in corporations all those years ago—are you satisfied with the progress we’ve made in the last generation?

More importantly: What’s the Communicator Manifesto you would deliver for the next?

***

Postscript: A letter from Bruce Berger, the writer of the original Communicator Manifesto:

The Communicator Manifesto ain’t dead, David, but it’s evolved in a world that appears ever more frantic and dangerous. Some days there’s sunrise in our work, and other days dense fog hides our progress, or stormy clouds and thunder dominate. Such is life, right? But we always need a manifesto in our field—a call to arms to address issues and concerns that arise in our profession in what today is a different world than that of 1995. And by 2050 there will be yet another dramatically different world. If we are still around. If the dramatized and dangerous politicians and world leaders haven’t imploded our planet. If we haven’t all asphyxiated from gassy oxygen-less air.

I agree, David: some things have changed in the last quarter century. Though working in academia, I’ve continued to consult and work on communication projects, and I’ve been involved with more than 35 research studies regarding leadership in our field, self-reflection, team building, listening, ethics, and so forth. Leadership has improved. For one thing, more leaders are women and people of color. More leaders today focus more on their employees and team members. They listen better. They are more sincere. They are more open to others and different ideas. They realize that diversity, inclusion, empowerment, engagement, and other popular words and phrases are MORE than just words. And more say “thank you” today.

Other changes also are underway. The workplace, highlighted or boosted by pandemic-related issues and changes, has given greater control to workers. There are more jobs out there, the strict 9-5 day is disappearing, more people work from home, salaries rise to fight competition, and more and more people at all levels appear to be more sensitive to the vital issues of trust, inclusion, diversity, equal opportunity, work recognition, and leadership that practices what it preaches in the real language of the heart, mind, and decision-making.

So, I’m more optimistic, David. I believe more of us across professions are embracing that “old” definition of the meaning of corporate work I shared in 1995:

We would like to find the most effective … most productive … most rewarding way of working together. We would like a work process and a set of relationships that meet our personal needs, too … our personal needs for belonging … for contributing … for doing meaningful work … for the opportunity to make a commitment … for the opportunity to grow and to be at least reasonably in control of our own destinies. And then, from time to time, we’d like someone to say, “THANK YOU.”

A new manifesto today might highlight trust, truth, information content, multiple channel presentations, and fake news issues. Or emphasize the desperate need for a new, third party in politics…

Thank you, David, for your thought-rich, wry, and witty contributions in this field.

Thanks, Bruce—for weighing in here and for writing the Manifesto in the first place. It was serious, idealistic, borderline subversive communicators like you, when I was in my mid-twenties, who convinced me corporate communication might be a field worthy of a life’s study. It has been! —DM

Leave a Reply