A couple weeks ago in this space, there was an interesting conversation about how to teach an inclusive American history that brings people together in a shared national narrative that’s not so depressing we all want to shoot ourselves.

(As boring as that sounds.)

You revise The American story by telling more complete versions of American stories—one by one.

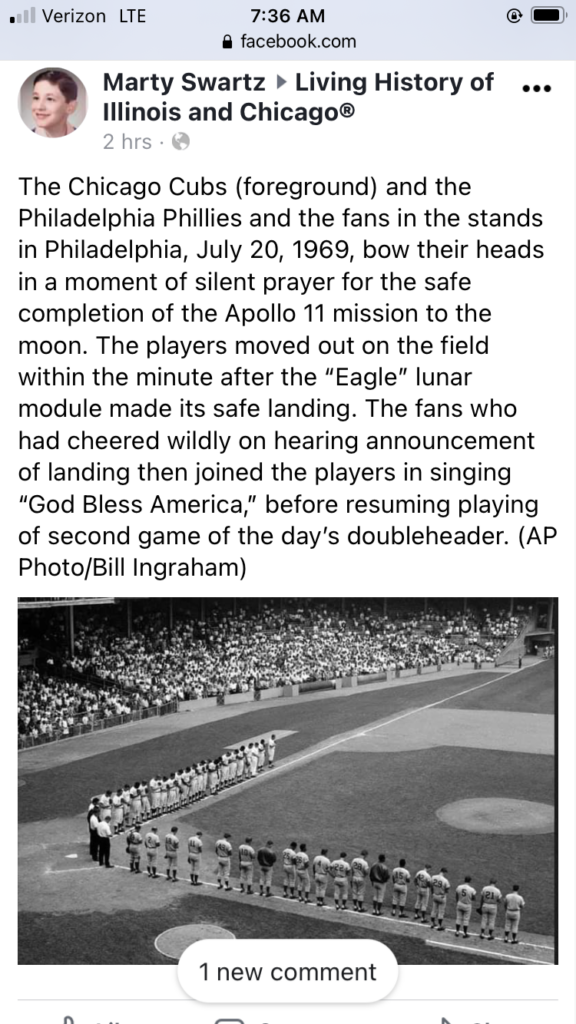

For instance, last week on the 52nd anniversary of the first moon walk, a local Facebook group ran this post, which might jar young people today, with its seeming sense of innocent national unity.

A whole baseball stadium of fans and players, praying and singing together as one? Wow! This must be what the old gaffers are going on about when they talk about American Consensus Lost.

But get ready to be surprised again, childerns, watching the (unbelievably fabulous) documentary Summer of Soul, where the people attending the Harlem Cultural Festival listened to an 18-year-old Stevie Wonder at the very instant the above ballpark prayer was taking place. And they told reporters they thought the moon landing was a waste of money that might be spent helping poor Black people, in Harlem. The movie quotes the Harlem poet Gil-Scott Heron, who wrote “Whitey on the Moon”: “I can’t pay no doctor bill (but Whitey’s on the moon) / Ten years from now I’ll be paying still (while Whitey’s on the moon).”

The recurring history lesson being that human beings do great things, human beings do terrible things, human beings here are oblivious to human beings there, nothing is ever nearly as simple as it seems, and if you’re going to be a responsible citizen of this country, you’re going to have to work all your life, going to have to be “woke” not once, but every morning you live.

And to the extent that you’re unwilling to do that, you will be marginalized—and you goddamn well should be marginalized, in an ever-roiling democracy like this.

But to the extent you are, it doesn’t have to be terrible and violent and mean and traumatic. It can be—as the above is to me—in the great American storytelling spirit that includes interrupting and saying, “no, no, baby, that’s not the place to start; you gotta go back to the beginning” … “sweetheart, that’s not exactly how I remember it” … “while you were laughing it up, you know what I was doing?” … “Hold up: You forgot to mention you were wearing assless chaps at the time.”

We’re used to that kind of raucous group storytelling in own lives, with our own family and friends, to add meaning and color and a more complete truth to the stories we know firsthand.

Then why are we so gobsmacked and offended when people ask us to do this kind of thing with history we know has been handed down to us in a simplified version by variably reliable narrators?

Leave a Reply