Everybody’s always talking about how terrible 2020 has been, even for the luckiest of us.

Together, we’ve never suffered through a year like this. But individually, I think many of us have. Most of us, maybe. In childhood, most likely. Even the luckiest of us.

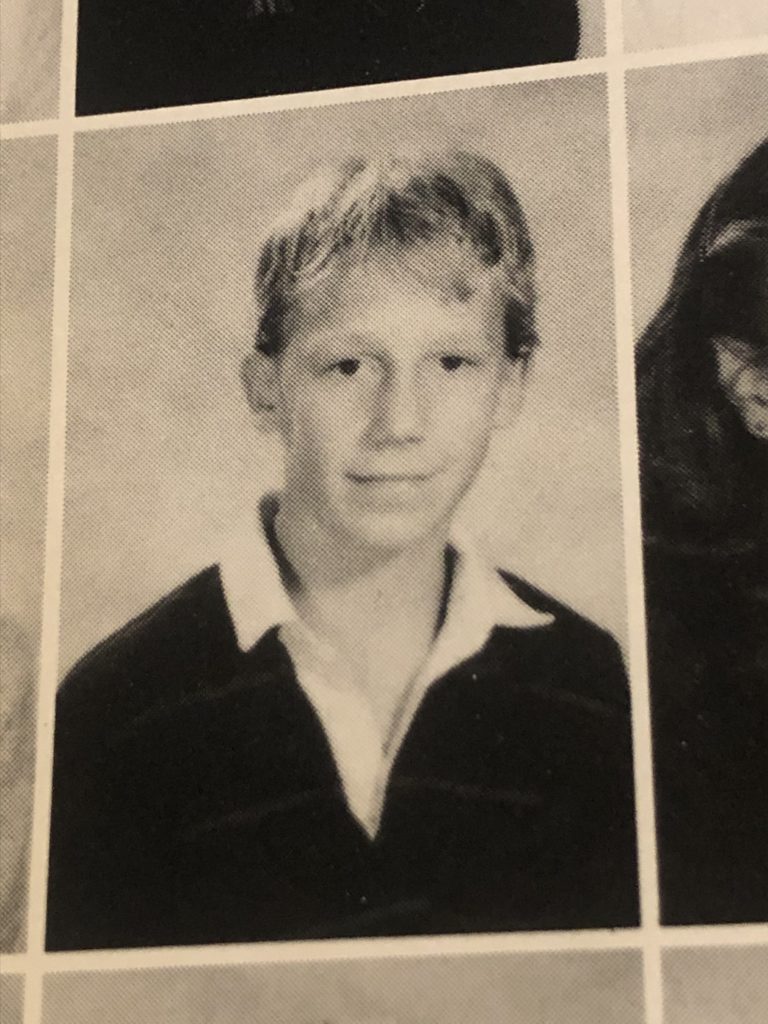

I had a few bad years in my childhood in a leafy, outwardly untroubled town called Hudson, Ohio. For example, I spent most of my junior year of high school locked in two adolescent drug treatment centers, and that summer visiting my mother in a psych ward. Not much of a tan that year.

But the worst was probably 1980.

It was my first year of junior high, which began with the universal terror of having to memorize a combination lock—and the unacknowledged understanding that last year you hadn’t needed a lock, but this year, you do. There must be dishonest and dangerous people, where you are going.

My sixth-grade homeroom teacher, Mr. Werbach, had a glass eye, and talked a lot about the potential devastation of a nuclear war, and specifically about the amount of total death one, two or three Soviet nuclear missiles could create if they landed in North America. In fact, I don’t remember Mr. Werbach talking about anything but that, except the day he told us one of our classmates had died of leukemia.

The math teacher, Mr. Shirhall, had a piranha who he fed guppies. He always made a show of it. As did the the piranha, who usually ate half the fish and left the other half twitching in the tank. Actually, I don’t remember if Mr. Shirhall taught math, or science. But I can see that twitching guppy like it was yesterday.

The language arts teacher, a woman whose name I don’t remember, showed us endless videos of bulldozers pushing dead emaciated Jews into vast graves, with very little context, as I recall.

I got terrible grades, and lived in grinding fear of taking report cards home to my parents.

I lived in grinding fear of all trips from and to the school building, mostly because Chris K— and Scott A— and a number of enthusiastic 11-year-old henchmen liked to toss me around on the playground. I wondered why. This was why.

Most searingly, on my walk home one afternoon, Scott A— harassed me all the way across the big field between the junior high and McDowell Elementary, where he was going to his Catholic CCD class. It was just the two of us. He wouldn’t let me pass. And I was too afraid to run, or to throw a punch. It was like two pawns struggling across the board, alone. It was so intimate. So pointless. So shameful. I would have much preferred a huge crowd around us laughing at me, because at least then I would have understood why it was happening. At least someone would be having fun.

I quietly told my dad once, on a dark winter evening as we walked the dog, and he just shook his head. I think he shook his head. Like I said, it was dark. He seemed sorry to hear it, to the point of wishing I hadn’t told him.

Weekends were my precious refuge. The year before, I had discovered sports—all sports, all at once—and in sixth grade I made it my joyful scholarly business to scale the sports wall at the Hudson Public Library learn everything there was to know about football, baseball, basketball, golf—everything! I believe I acquired more raw knowledge in that year than in any other year of my life, all the while getting Ds in social studies.

That year the Cleveland Browns were known as “The Cardiac Kids,” because of their many last-minute victories, all engineered by a little, weak-armed quarterback named Brian Sipe who, surrounded by all those giants, looked to me like me. That year the Browns were compelling enough to pull even my dad away from his Sunday puttering. He and I shouted and hugged and slapped high-five while our confused Springer Spaniel barked at us madly and my alarmed mother shouted from the bottom of the stairs, “What the hell is going on up there?”

But I didn’t have any sports friends yet. My only friend was a D&D and Erector Set nerd, who had for years threatened to stop being my friend if I kept swearing so much. So after the Browns game ended, I would sprint out the back door into the fading fall afternoon light and kick the football straight up into the air in our big backyard, catch it on the bounce and run and spin and dive over the goal line, a sunken stretch of drainage tile between two trees. I would come to dinner mud-covered, and as happy as I could be with a Monday school day looming.

It seemed to me my parents were always mad at me. I learned when I became a parent that that meant they were worried about me. My mother lamented in a letter to a friend when I was in junior high—a letter I read just a few years ago—that I must be having a hard time measuring up to such talented parents as she and my dad. No, Mom—it’s hard for every kid to measure up to every parent. My dad remembered lying under his family’s dining room table as a boy, looking up at all the pictures on the wall, the cabinets, the china, the chandelier, and wondering, “How on earth am I going to get all this stuff?”

A kid has absolutely no sense that these problems are only temporary, that these worries are everyone’s worries. A kid can see only that these troubles are gathering. A kid can only try to make life bearable today. “When you reach the end of your rope,” went a popular poster slogan around 1980, “tie a knot and hang on.” Where was that line, this last April, when we needed it?

During 2020—at night, with a glass of wine or bourbon, I have found almost every 1980 Browns game on YouTube, and watched every one in its entirety, except for the last—the playoff played on a frozen field in four-degree weather and 16 m.ph. winds. When my hero threw a senseless interception at the last minute and cost us a chance at the Super Bowl, and I went out of the room to get out of my dad’s sight and sat on the stairs and cried.

So, in terms of trauma—snowballing bad news with seemingly no meaning or moral. No end in sight, and humiliatingly little to do to help ourselves. And no sign of sane adults to save us—this year hasn’t felt unprecedented to me. It has felt to me like the worst parts of my childhood.

And this Thanksgiving—as we finally glimpse a little good news, as we allow ourselves to think about an end to the worst of this madness, as sensible grown-ups begin to appear on the playground—I’m thankful for that.

And hopeful that I won’t soon have to live out another year that makes me relive 1980, again—that makes all of us live out our own 1980s, again.

Even the luckiest of us.

Wonderful piece. Took me back to my own childhood. Thank you.

Phew, Jim. I was hoping no one came on here and said, “Childhood uncertainty and fear? I don’t know what you’re talking about?”

In addition to the personal hell that still hovers over you 40 years later, 1980 offered a dose of political misery that you were likely too young and too preoccupied to take note of then but can fully appreciate now: An incompetent and mean-spirited clown was elected president in a landslide.