I stopped in Mendota, Ill. for gas and Gatorade last Tuesday morning on my motorcycle ride from Chicago to Des Moines, and checked my phone. Grandpa had started a family group chat with this cheerful missive.

I’m beginning to think that you all need to move to Thailand rather than us move to the US😞😞😞

I find it difficult to even watch the US news anymore

I knew that we have been dumbing down for last few generations but had not realized just how bad it was getting

I’m guessing it will take the US many years to recover. feel sorry for you guys and the kids

Searching the store for sunflower seeds, I couldn’t imagine what he might be talking about.

Turning west onto Route 92, I decided I would chronicle this trip to see beloved Iowa family for the first time since Christmas, as a reply to my father-in-law, whose views as an American and also as a citizen of the world one almost has to respect. He grew up on a farm outside Marshalltown, Iowa, he served in Vietnam, he managed vast construction projects all over the country and then all over the world (including Thailand, where he fell in love and wound up retiring). And he raised two kids whose children he now feels sorry for because of what America has become.

What has America become? I always feel more able to think on that broad topic outside my crowded Chicago environs, in the wide Midwestern countryside.

“Your TV isn’t a window,” was the first retort that tumbled into my head as my Triumph daydreaming machine scattered birds between the cornfields, the morning sun behind me and my shadow outrunning my front wheel ahead. Yeah, if all I saw on CNN was all I saw of America, I’d feel sorry for Americans, too. (For instance, on the TV this week was ICE’s plan to train citizens to arrest immigrants, the commuting of Roger Stone’s sentence, a vicious return of Covid cases and an education secretary’s call to return students to classes irregardless—a word last week accepted by Merriam-Webster.)

Another observation that came to me over the din of the engine and the wind: The most ignorant and classless Americans are surely the most ignorant and classless people in the world. (In the Netherlands, do they have bumper stickers for sale in gas stations that say in Dutch, “I’m only speeding cause I have to poop!”?)

But the wisest and finest Americans are as wise and fine as anybody anywhere, and I know a lot of them personally. Those Americans are everywhere, taking care of their families, worrying like hell about their kids, paying their bills, facing down financial hardships and still, judging from the margins of the skinny roads I rode, trimming their lawns to tidy perfection.

As I reached the Mississippi and ran southwest along its eastern bank, I looked for lunch and knew this task would be complicated by more than Covid restrictions. I spotted sort of a makeshift outdoor bar on by the river, a bunch of guys sitting around it. Five years ago I probably would have pulled into the parking lot and ridden up to ask if the place served burgers. Even though it was noon, I felt like I was in the wrong neighborhood after dark, so I kept riding. Hashtag, whenevenwhitemalepriviledgeisn’tenough.

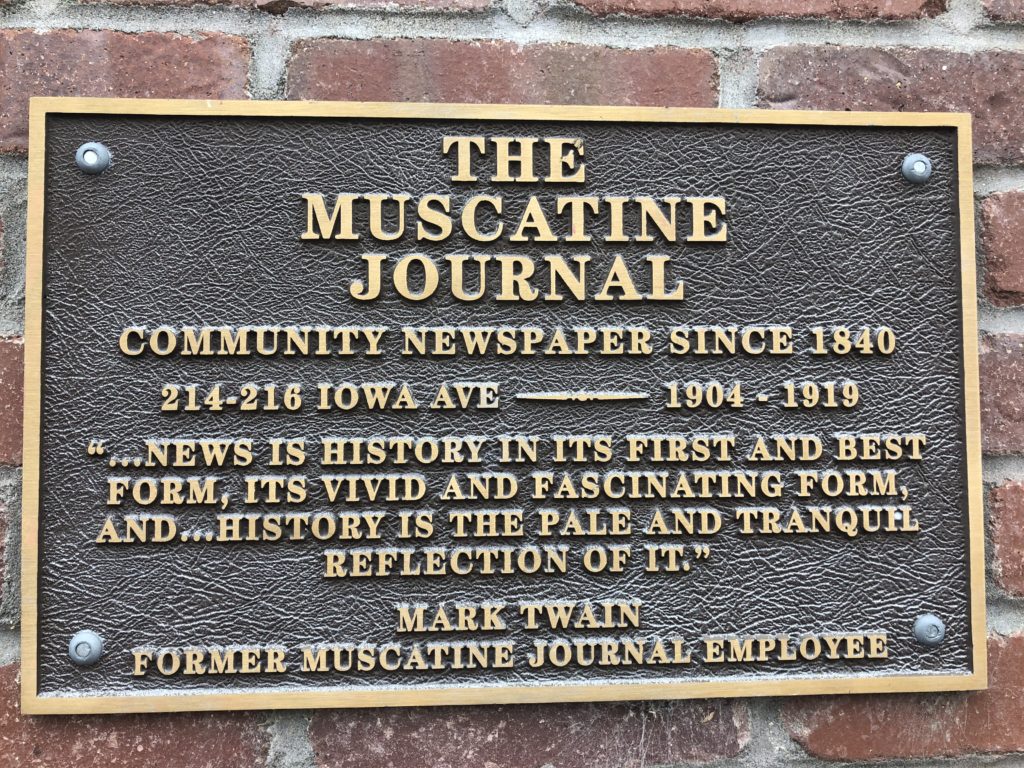

I crossed the river at Muscatine, Iowa, and found a bar called “Boonies” with an outdoor patio and a comforting plaque on the wall.

Outside, the owner, in a mask—masks were about 50/50 in rural Illinois and Iowa, from what I saw—kibbitzed with a couple of customers, one of whom was from also Chicago. Like they do everywhere, they talked about Covid, and masks, and social distancing, and schools, and risks. (“It’s really complicated,” a masked woman told an unmasked gas station clerk in Shabbona, Ill. on my ride home. “It sure is,” the clerk agreed.)

And didn’t I know about risk. Here I was riding a motorcycle hundreds of miles—my wife and daughter followed the next day—to gingerly visit some of the most precious people in all of our lives, one of whom has had lung cancer twice, in a state whose cases were skyrocketing. And if you’d have asked us why now, we couldn’t have come up with a much better answer than, “We just need to.”

After 10 hours of riding, I saw my first Black Lives Matter sign—and my second and third and 10th—about two tenths of a mile from my destination, in a leafy neighborhood in Des Moines.

My 10-year-old niece ran out. “Are we allowed to hug?” I asked. “My mom said it was okay,” she answered. And she put her arms around me tenderly and all the social distancing promises began to melt into social distancing compromises, against the slow-warmed soapstone of long-denied family love.

Over the next days, we would all learn more about that. And America, too. Tomorrow, I’ll write about that here.

David — I look forward to reading more.