I attended Kent State University over a period of years that included the 20th anniversary of the shootings there in May 4, 1970. So I tend to think about Kent State around this time of year. But never has the Kent State story connected as directly with current events. Thanks to protests on the Israel/Palestine issue, college campuses are in more intense and widespread turmoil this week than at any time since the Vietnam era.

“The decibel of our disagreements has only increased in recent days,” Columbia University President Minouche Shafik wrote in a memo today, canceling in-person classes in what turned out to be false hope that tempers would cool after virulent pro-Palestine/anti-Israel protests roiled campus over the weekend. She added, “I know that there is much debate about whether or not we should use the police on campus, and I am happy to engage in those discussions. But I do know that better adherence to our rules and effective enforcement mechanisms would obviate the need for relying on anyone else to keep our community safe. We should be able to do this ourselves.”

Harvard has closed Harvard Yard until Friday in anticipation of more protests. Yale, NYU, MIT and University of Michigan are among schools whose administrators are grappling with what to do about sit-ins and tent encampments on their campuses. Protesters are being arrested and so are others protesting with them. “Dozens of police officers have begun making arrests at NYU,” wrote a The New York Times reporter on the scene tonight. “The scene is disorderly. The officers are pressing up against a crowd of a few hundred people, grabbing protesters that refuse to move.”

What is happening?

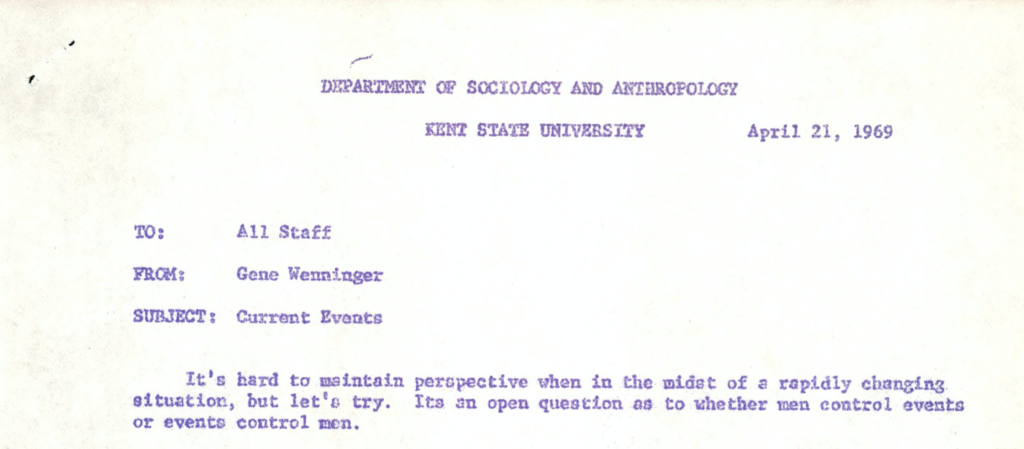

Gene Wenninger was Chairman of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Kent State University, and the memo was to his colleagues, almost exactly about a year before the Kent State tragedy.

Can we learn from Wenninger and his colleagues’ attempts to avoid a worst-case scenario at Kent, more than a half century ago? Let’s try.

I discovered Wenninger’s memo in the collected correspondence of Thomas S. Lough (pronounced “luff”), a Kent State sociology professor who held a bleeding student in his arms that day, who was later indicted over his involvement with student protesters—and who woke me and my classmates up to a few things, in a Kent State course a couple decades after later.

In his memo, Wenninger ruminated about antiwar tensions on campus, and the administration’s attempt to back a Kent State student activist group less radical than the KSU chapter of the notorious national organization, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). After acknowledging the difficulty of assessing a fluid situation, Wenninger wrote:

What we’re in could turn out to be either a triumph for the moderate students or continuing trouble for the University. There is no doubt in my mind that many changes are needed in our society, particularly changes that will provide a vital place for our youth. No disagreements here on the need for change.

But how to get enduring and genuine change? The SDS has several sets of answers, depending on which wing of the movement you examine. I do not want to get into an ideological debate. The immediate problem is not ideology, but tactics. …

What about K.S.U.? My own feeling is that we have here a well-intentioned but overly complex administrative set-up which rates consistently behind poor in the area of human relations. It is not an oppressive administration by any means, but rather does not understand what motivates student concerns. The environment in which the University operates, the county and state, are increasingly hostile toward the University and toward student demands. The Legislative mandates of last summer, those now in the mill, the editorials in local and regional mass media all indicate this hostility. The University is caught between the public and the students, responsible to both but not able to satisfy both in most cases. …

Wenninger concluded by advising the faculty to “keep up with the literature circulated by all parties” including “the administration’s arguments. … Meanwhile, stay up on events, talk with students, stay cool, and hope that things work out.”

Almost exactly a year later came the campus unrest that brought the National Guardsmen—who committed the shootings that would make the words “Kent State” mean: American soldiers murdering American youth.

Lessons might also be taken from the aftermath:

In the U.S. government’s effort to explain the unthinkable massacre, a grand jury cleared the National Guardsmen who had fired their M-1 rifles down from Blanket Hill into the crowd.

From The New York Times:

The report fingered the university’s administration for fostering “an attitude of laxity, over‐indulgence and permissiveness,” accused some faculty members of an “over‐emphasis” on “the right to dissent,” and criticized students for their behavior and allegedly “obscene” language.

The cries, the report said, “represented a level of obscenity and vulgarity which we have never before witnessed!” The jury continued: “The epithets directed at guardsmen and members of their families by male and female rioters alike would have been un believable had they not been confirmed by the testimony from every quarter and by audio tapes made available to the grand jury.” …

At a brief news conference late this afternoon, the university president, Robert I. White, said “I appear before you rather well battered.” Then he urged calm.

The grand jury charged people who came to be called the Kent 25—two dozen students and a single professor, Tom Lough—for inciting the events that led to the protest that gathered the crowd into which the National Guardsmen fired. Those charges were eventually dismissed.

I happened to have Dr. Lough for a sociology course, in 1989. He spent much of that semester teaching us exactly what he had explained to a correspondent in 1975, who had asked him how the Kent State shootings had affected his life and outlook.

“As the years have gone by,” Lough wrote, “the evidence seems increasingly to point to the likelihood that the whole Kent State affair … was planned and executed by the government—certainly the state government, but probably in collaboration with [U.S.] Attorney General [John] Mitchell. I suspect it was planned initially in Washington, D.C.”

In order send a message to student protesters on campuses all over the country, the theory went.

Lough continued:

As for the effects all this had on me …

It’s true that I now think the U.S. is beyond salvaging, and that I have become convinced about its being a lost cause over the last four years. … During the middle and late 1960’s there was a kind oof electricity in the air that led many of us to believe we might just be able to turn this country around. In spite of all the busts and outrages, there was hope. But those 13 seconds of gunfire at Kent State seemed to signal the beginning of the end of this radical movement, and now the radicals seem to have given up. To be gassed, beaten and jailed for peace and justice is one thing, but to be shot and murdered is another. The feeling among students who five years ago might have been radicals is that the U.S. is not worth trying to save. The sad fact is that the U.S. needed the radicals, whose analyses have proven totally correct for 15 years, far more than the radicals needed the U.S. And now that the U.S. has succeeded in stamping out the political vitality of the nation’s youth, there is no longer any hope. It’s just a question of standing aside and watching this huge mindless brute smash itself to pieces, staggering and flailing without vision or purpose. … Kent State was a symptom of something much deeper. … The fact is, we’ve had it.

Tom Lough died in 2008, but little about 2024 would surprise him, I guess.

It’s post-adolescent students enjoying far more moral clarity than adults (some of those students being extreme post-adolescents).

It’s well-meaning institutional leaders trying desperately (and often failing) to maintain a constructive dialogue in a disintegrating society.

And it’s all manner of hostile and opportunistic (even murderous) politicians and other gadflies, who profit emotionally or politically or economically from placing blame for unrest solely and lazily on young activists and beleaguered leaders of institutions as, and punishing or dismissing both accordingly.

You could say it’s depressing. (Nothing ever changes.) You could also say, in a way, it’s reassuring. (It was ever thus.)

Whatever it is, “we’ve had it” isn’t the thing to say now any more than it was the thing to say then—however strongly it was felt. It’s the flip side of “make America great again”—and thus, just as clumsy and unproductive.

As Gene Wenninger did in his memo, written nine days before my birth—I find myself hoping, too: May the protesters maintain sanity, the administrators, equilibrium—and everyone else, a healthy fear of a terrible historical parallel.

Leave a Reply