Occasionally I take full advantage of the fact that this is my own blog, and I can write here whatever it is that I want—even though I know full well: Not if I want regular readers, I can’t.

And yet, today I do hope you’ll join me as I narrate and culturally commentate on an obscure Monday Night Football game between the Cleveland Browns and the Dallas Cowboys, in 1979. Obscure, but significant to me, because it took place exactly a year before I found my own imagination, my own curiosity, my own love of history and my Sunday comfort—in sports in general, and pro football in particular.

To set the scene, here’s excerpt from a Huffington Post piece I wrote six years ago during the height of the now-faded NFL concussion controversy, on my relationship with football.

I was a kid before ESPN came along and injected sports into every home.

Our Hudson, Ohio home had music, so I took piano lessons. Dad was into antique cars, so I went to car shows. Both my parents were into horseback riding, so I did that. I didn’t know about sports, beyond the cultured-sounding “human drama of athletic competition,” which we saw some Sunday afternoons on ABC’s Wide World of Sports.

But when I was 11 years old, I suddenly and totally fell in love with football. I vaguely associate this cataclysm with a “math football” competition among the homerooms in fifth grade at McDowell Elementary. Playing for Mrs. Anderson’s Dolphins, maybe I figured that if football could make math fun, it could make everything fun.

It sure made reading fun. Every afternoon I rode my bike to the Hudson Public Library until I’d read everything they had on the NFL. I don’t remember checking the books out. I remember reading them in the library, and hearing in the silence the roaring echoes of real stories about magic men with magic names. Johnny Unitas. O.J. Simpson. Bart Starr. Jim Brown. Gayle Sayers. Joe Namath.

For a boy growing up in a WASPy little Ohio town where everyone was named Murray or Sullivan or Butler or Keane, these men’s names were as strange as anything from Tolkien. Bronco Nagurski. Red Grange. Curly Lambeau. Big Daddy Lipscomb. Bambi Alworth. Roman Gabriel. Sam Huff. Ray Nitschke. Chuck Bednarek. Dick Butkus. Hell, Zeke Bratkowski!

I read about The Sneaker Game, the Heidi Bowl, the Ice Bowl, the Immaculate Reception, Wrong-Way Regal, Ghost to the Post, The Longest Game, the Sea of Hands, the Perfect Season and The Greatest Game Ever Played.

I gaped at the pictures of the sun-splashed September grass, the crisp-clear October air, the mud-caked men of November, the frozen granite fields of December and the Super Bowl palm trees of January.

It was all impossibly rich—and to me, impossibly beautiful.

As bewildered as my parents may have been at my Fosbury flop into football history, they must have been glad to see me spending so much time at the library.

Maybe as a form of encouragement, my dad started watching Cleveland Browns games with me on the big color RCA TV, up in my parents’ bedroom. Our English Springer Spaniel had lived the first few years of his life in a civilized house, and so when Dad and I would yell and slap high-five, the dog reasoned that a fight had broken out. He would bark madly, shattering the Sunday afternoon peace and prompting shouts from my startled mother, at the bottom of the stairs. “Jesus! What’s going on up there?”

Incredible things were going on up there. That year, the Browns happened to have a season seemingly made for me.

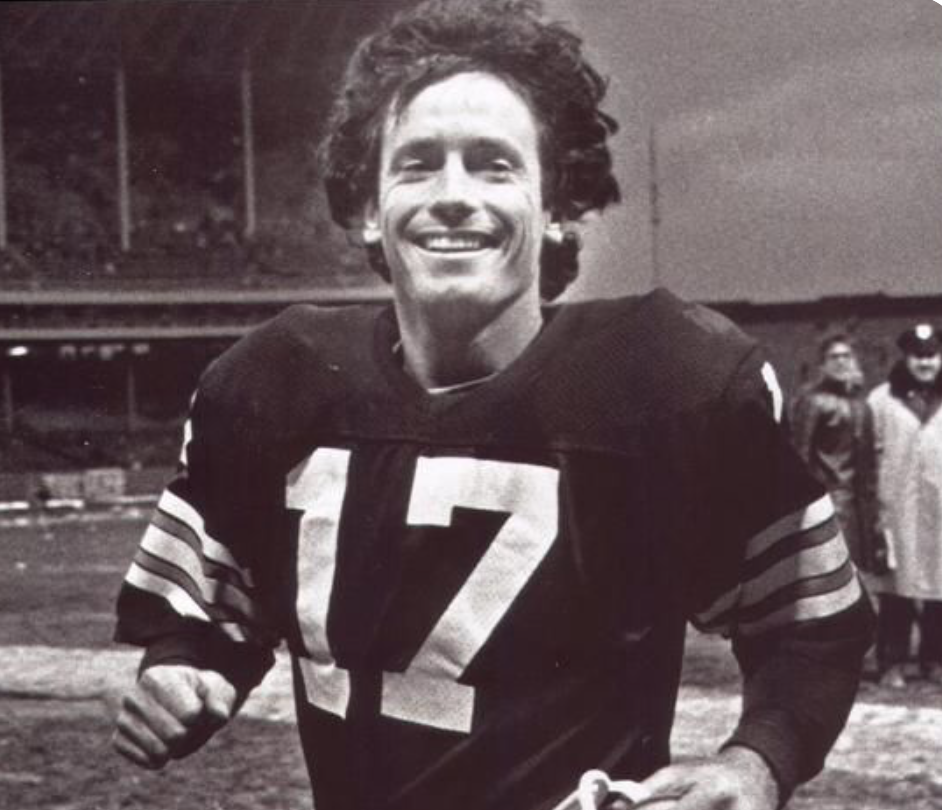

Brian Sipe was a fragile little quarterback that an undersized 11-year-old could relate to. With a black rubber sleeve protecting his weak right elbow, Sipe heaved the ball over the offensive line like a shot-put over a woodpile, and it somehow wobbled into the waiting arms of enough resourceful Browns receivers that Sipe somehow won the MVP of the American Football Conference that year.

That wonderful team was known as the Kardiac Kids, because every victory was last-minute. (And so were the losses.) I could go on about the Kardiac Kids, and their coach, Sam Rutigliano, a kind of Phil Donohue figure who said things like this, after a tough loss: “There are 800 million Chinese who didn’t even know we played today. We’ll get over this.” I could name every player on the roster, right down to Dino Hall, the short, slow, butterfingered kick returner who we loved anyway. In fact, it is very hard for me to stop writing about that team. Let’s move on, before we get to the bitter playoff loss against the Oakland Raiders, when Sipe threw a terrible interception in the back of the end zone when all we had to do was kick a short field goal to win the game and I walked out of my parents’ bedroom and sat on the stairs and sobbed.

***

The Browns were actually being called the Kardiac Kids starting in 1979, when they won a bunch of games coming from behind, before they faded to a 9-7 record and missed the playoffs. Early in 1979, they played the Dallas Cowboys on Monday Night Football, at Cleveland Municipal Stadium, a gigantic drafty dump of a ballpark where fans were as likely to get tetanus or lead poisoning or mesothelioma or pneumonia as the Browns or the Indians were to get a victory. But in Cleveland, on its absolute ass at that time as steel jobs drifted down the brown Cuyahoga River, the Indians and the Browns were the only hope we had. And the Indians had finished in sixth place in the American League East. So it was down to the Browns.

As I’ve said, I didn’t start watching football until 1980, so I didn’t see this game.

But I’m watching it tonight. Won’t you join me?

***

“They’ve been waiting in Cleveland, Ohio for this night for a long time,” is Howard Cosell’s opening line. “Excitement prevails in this usually troubled city. There is a capacity throng on hand at Municipal Stadium. Why? Monday Night Football and a battle of the unbeatens, Dallas against Cleveland!”

Unbeatens, yes: Both teams were 3-0. But Dallas had a roster full of royalty. Two-time Super Bowl winner Roger Staubach, and the classy running back Tony Dorsett. The Browns? “Underrated quarterback Brian Sipe,” as Cosell described him. And at running back? “The little water bug from Oklahoma, Greg Pruitt.”

It was kind of an honor that the glamorous Cowboys and their bespoke coach Tom Landry even agreed to play a game in this old stadium, with its crummy locker rooms where the visitors’ showers sometimes ran cold.

“The noise here as you can hear is utterly deafening,” Cosell says. “I haven’t seen this kind of excitement in this ballpark since 1948, when for the first time in 28 years, the Cleveland Indians became the world champions of baseball. The people in Cleveland believe in this Browns team.”

***

And we go to commercial: Radio Shack. And Miller Lite: “Taste Great, Less Filling,” starring Rodney Dangerfield and a huge cast of sports has-beens.

***

Browns get a big kickoff return, and the crowd is indeed roaring like the waves off of Lake Erie.

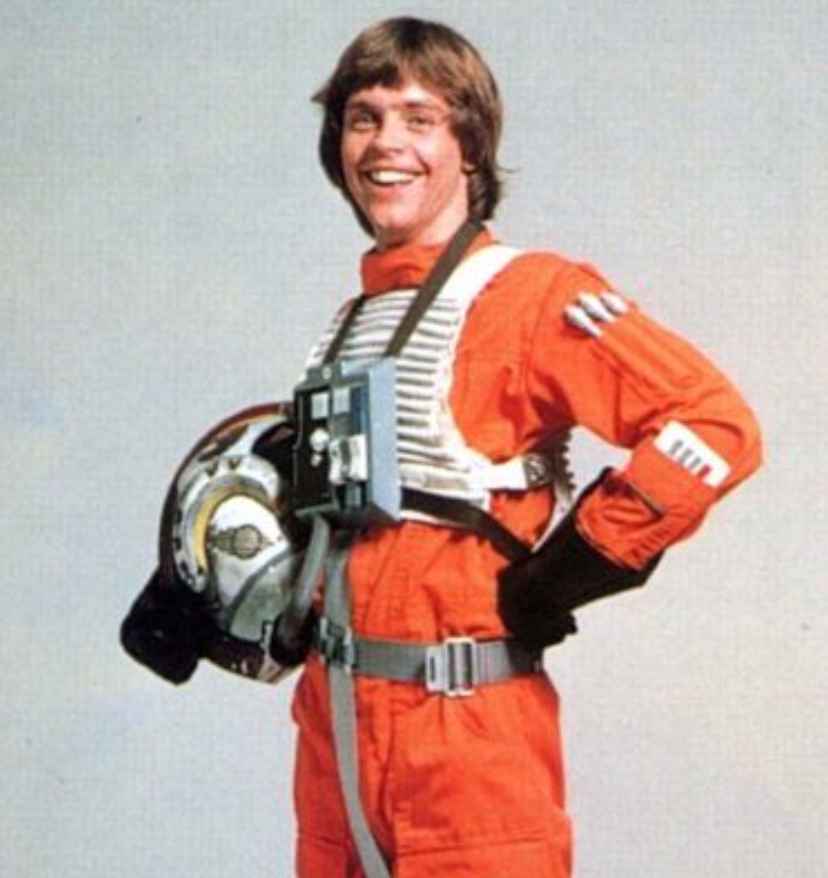

Sipe brings ’em up. I’ve never heard anyone else make this connection before, but I know that every kid of the era understood it subconsciously:

Brian Sipe was Luke Skywalker, and the Force was with him.

And I’m goddamned if he didn’t trust his feelings and take the Browns down on the opening drive and throw a touchdown pass to Dave Logan to put the underdogs ahead, 7-0.

***

Commercials: “Buick proudly announces some very fine cars. And some very good thinking.” And a promo for a heavyweight boxing match.

***

The Browns give Dallas nothing, forcing them to punt.

***

A commercial encouraging viewers to join the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines. And a reminder that, “like a good neighbor, State Farm is there.”

***

The Browns have punt again, and you just have to hear Cosell pronounce Reggie Rucker’s name: “Ruckah.”

Goodness gracious, Skywalker just escaped a sack and heaved the ball 50 yards for another touchdown, deep down the middle, to Ozzie Newsome. Missed extra point, 13-0.

***

Miller Lite, again. And Oilers running back Earl Campbell, on a beach, promoting Skoal dipping tobacco, and grab-ass. As he heads toward some sexy ladies, he says: “I think I’ll play some touch.”

***

We learn that former President Gerald Ford is in attendance tonght, the guest of Browns’ owner Art Model.

***

Thom Darden—whose autograph I would later cherish—just intercepted a Staubach pass and returned it for a touchdown. 20-0. Forty-two years later, and 30 years after moving to Chicago, I’m losing my mind, cheering out loud.

And I still think we’re going to lose.

And Roger Staubach just hit Tony Hill with an elegant bomb. Their touchdowns look better than ours.

The Browns take over, leading 20-7, get nothing done on offense, and bring in a kicker who sounds like a country singer, and kicks like one, too: Johnny Evans. The Cowboys start with great field position, around their 40-yard-line.

***

I mean, who wears orange pants? The person at the party who’s trying to be funny, that’s who.

I know the Browns won some championships in the middle of the century, but never while wearing orange pants; they wore white pants back then, because they wanted to win. Do you think the New York Yankees would have won 27 World Series, in orange? This is not a serious team’s uniform.

***

“Tonight, let it be Lowenbrau.” RCA color TVs show you what Jupiter looks like. Oh, and Jimmy Stewart pitches for Firestone tires—a commercial my own adman dad made (and the first commercial Jimmy Stewart ever did). Yes, I’m enjoying myself tonight.

***

O.J. Simpson, for Hertz. A commercial for The Amityville Horror.

***

We’re in the second quarter, the club in the orange knee pants still leading 20-7 over the one that looks like a noble military force. And as I type it, the former Midshipman Staubach throws a perfect bomb from midfield, this time to Drew Pearson, who goes out of bounds at the Browns’ four yard-line.

Here we go.

But then!

Tony Dorsett fumbles! The ball is recovered by the Browns’ Dick Ambrose!

You heard it right. Tony fumbles, and it’s recovered by Dick. Are there any Tony’s left in the NFL? I’m pretty sure there are no Dicks.

In any case, the Browns take over, still leading by 13.

***

A commercial for Boeing jets. A song: “The world feels a whole lot better when the people of the world all get together. The world feels a whole lot better when we all get together.” We’re reminded that the next time we fly, we should “remember to fly Boeing.” And how would we go about doing that? What was the marketing strategy here, to spend all the profits before the end of the fiscal year?

***

After another cowboy-boot punt by Johnny Evans, Dallas has the ball at midfield again. Staubach hits Tony Hill at the Browns’ 25.

But Dallas has to settle for a field goal attempt, which is blocked.

Somehow, the Browns still have a solid lead, with just over three minutes left in the first half.

***

A commercial for the “Lanier No Problem Typewriter.” (“It does more than just type.”) And a Miller High Life commercial that shows land surveyors working in the mountains; they ride their helicopters home at the end of the day to drink “the best tasting beer you can find. If you’ve got the time, we’ve got the beer.” These beer commercials trained Americans from a very young age that adult life was about working hard all day, for a reward at the end, in the form of liquid drugs. And boy oh boy, did they train us well. I happen to have a bottle of red at my elbow right now.

***

The “frustrated Cowboys” have the ball back with two minutes left, Frank Gifford narrates. And they go nowhere, having to punt.

Howard Cosell is interviewing Jerry Ford, who tells us that the Browns are leading an exciting game, demonstrating his trademark magnificent grasp of the obvious. “Thank you, Jerry, you look superbly well,” Cosell says.

***

“Being retarded doesn’t mean you can’t reach out and hold onto life,” says Cowboys tight end Billy Joe DuPree, at the outset of a commercial for the United Way.

***

It’s halftime. I’m halfway through the bottle of wine. Commercials for United Airlines (“Fly the Friendly Skies”), and also for TV shows Charlie’s Angels, Eight Is Enough and Tic Tac Dough.

***

The Browns and Cowboys trade punts for much of the third quarter. Brian Skywalker is hit so hard by Thomas “Hollywood” Henderson that he’s seen on the bench administering smelling salts to himself.

***

A commercial for Goodyear Tiempo, the official tire of the 1980 Winter Olympics.

***

Dallas is threatening, at the Cleveland 42, but Vader throws another interception.

***

A nurse talks about how happy she is with her Buick Skylark. And for a tugboat captain, “Now comes Miller Time.”

***

A Browns’ drive stalls. Ladies and gentlemen … Johnny Evans!

We’re still in the third quarter, the Cowboys have the ball, and I still believe the Browns are going to lose. Except: Staubach fumbles, and the Browns recover! Cleveland football, at their own 45. Now they’re on the Cowboys’ 40. The bad news, we learn that Greg Pruitt (“the little water bug from Oklahoma”) has a knee injury and will not return to the game. On the other hand, the ABC camera alights on a sign that says, “The Browns are as strong as ‘The Hulk.'”

We move to the fourth quarter, Browns still driving, down to the Cowboys’ three yard-line.

I’m starting to think the Browns could win. Touchdown, Browns! Extra point missed, Browns lead 26-7.

Don Meredith threatens to sing his signature cover of Willie Nelson’s song, “Turn Out the Lights, The Party’s Over.”

***

General Motors: “People building transportation to serve people.” (As opposed to Ramada Inn: “Nice people taking care of nice people.”)

***

A shot of Art Modell. Cosell says in a combination of self-aggrandizing self-effacement, “I’ll tell ya something. He grew up with me in Brooklyn. He became successful.”

***

A bunch of guys dynamite a tunnel through a mountain. “Now comes Miller Time.”

***

Staubach is sacked, and this is turning into an old-fashioned ass-whipping. And he’s sacked again. We’re halfway through the fourth quarter, and it’s all over but the shouting. (Mine.)

***

The orange is a comfort. The orange is optimism, without expectation. The orange is a sense of humor. A shot of Sam Rutigliano, in an orange sweater. “What a nice man,” Don Meredith says.

***

At this moment at about 11:30 p.m. on the night of September 24, 1979, I was 10 years old and fast asleep. Within a year, football, in all its imbecility and beauty, would be my window into to everything: cultural, economic, historical, political and psychological.

***

As the last seconds wind down, Coach Rutigliano is ranging his sideline, shaking hands with his players. What a happy night.

Like I said, the Browns slumped to a mediocre record in 1979, and then broke their fans’ hearts even more profoundly the next year. And twice more (or three times, I can’t bring myself to remember) later in the 1980s. Then Modell moved them to Baltimore, leaving Cleveland to pull itself up by its own bootstraps—which it did, despite the return of a team unworthy of any of the above.

The Browns are better now. Will we ever win a Super Bowl, before I and my friends die? I think I speak for all of us when I say, it would be a pleasant surprise. Until then, we’ll subsist on a few fuzzy, orange-accented memories.

Leave a Reply