Working on my apologia for “stakeholder capitalism,” I made a notation I wanted to get back to: “I do think modern CEOs think they invented corporate compassion.”

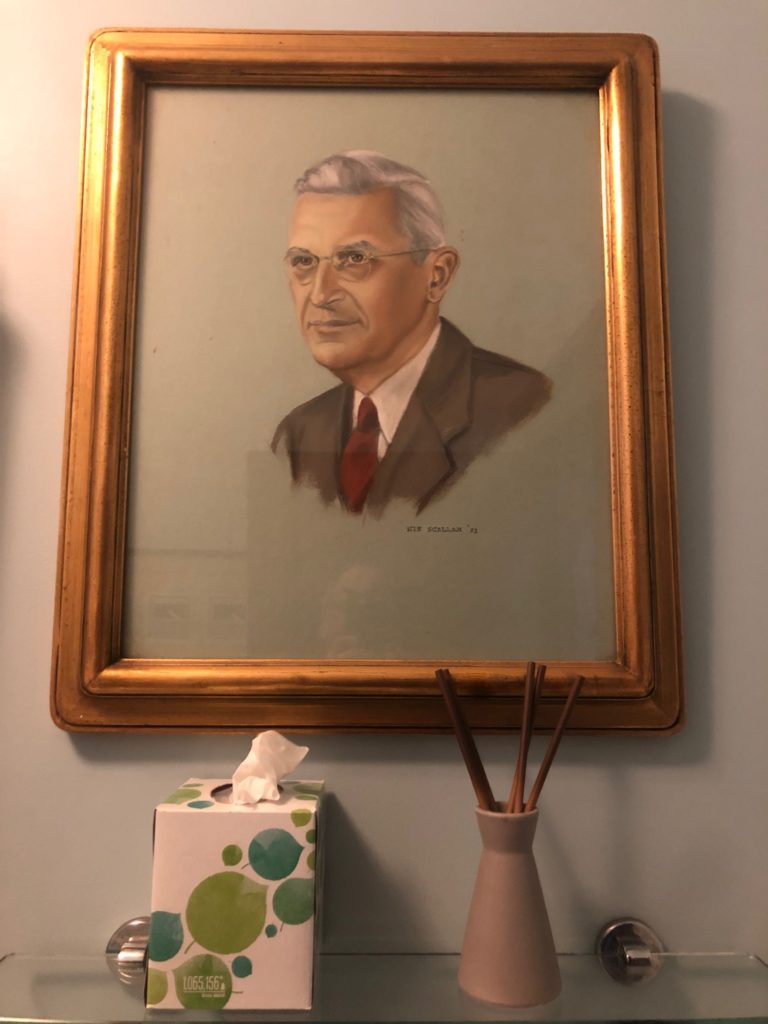

Stakeholder capitalism would not have been hard to explain to my dad’s father, who ran public relations and personnel at Armco Steel in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s. Armco built the nation, served the war effort, then went back to building the nation—all while employing a whole town-full of human beings, some of whom turned up at Charles Murray’s side door when they needed a new community swimming pool, a library, or just money for somebody’s wife’s cancer operation.

Armco peacefully deflected the steelworkers’ union by encouraging a shop cooperative, instead, with its own bargaining power. Armco offered a “bill of rights” for its stockholders, employees, management, customers and the community, and was early to provide an eight-hour workday, healthcare coverage and pension plans.

So actually, the need for a term like “stakeholder capitalism” might have confused old Gaga. But then, he would have a lot of questions these days, including: “Why is my portrait in your bathroom?”

But in general, the idea of social responsibility and taking care of employees seems anathema in our consensus memory of 20th-century corporate life. And no, The Organization Man wasn’t known to call out for a “mental health day.” But I do think that even those bad old corporate departments and supervisors found a way to carry along their people when they needed it.

My dad prided himself on that, in fact. He told the story about when he was a very young supervisor at Frigidaire, in the early 1950s. A middle-aged secretary burst into tears in front of him one Friday when he told her she was reassigned to a windowless office. That hadn’t been his decision to make, and it wasn’t his to reverse. Upset, he went to his own supervisor, who advised him to commission the art director to spend the weekend painting on the secretary’s blank wall, an outdoor mural scene, to look like a window. When she returned to the office on Monday, she cried again—tears of joy.

That sort of thing obviously wasn’t Frigidaire corporate policy—but good people found ways to take care of their best people. Why? Because as my dad also used to like to say, “There is nothing like a good man or woman.”

An excerpt from a wee memoir I wrote about my dad’s advertising career, Raised By Mad Men, tells you how people took care of each other, even in the most extreme circumstances, even in an ad agency nested in the marble fortress of the General Motors Building at the height of GM’s power:

Though Carol Meuhl shined at work, darkness had descended at home in Ann Arbor. Her brilliant husband Jack was manic-depressive and addicted to drugs and had become violent. There’s a story about a dinner party they threw in honor of a visit from the celebrated Chicago novelist Nelson Algren. The young bride made sole piccata with grapes. Her husband declared it inedible and threw the platter on the floor in front of Algren and all the other guests.

Once he threatened her with a gun. She said she was leaving him. He said that if she did, he would commit suicide. She moved out. He committed suicide.

“Carol’s back,” Tom Murray wrote to creative director Kensinger Jones Sept. 3, 1963. “She’s supposed to take it easy for a while so we’ll handle it this way. She’ll be in most weeks four days. Sometimes she’ll take two days off. If OK with you, we’ll handle it this way without saying anything to anyone else.”

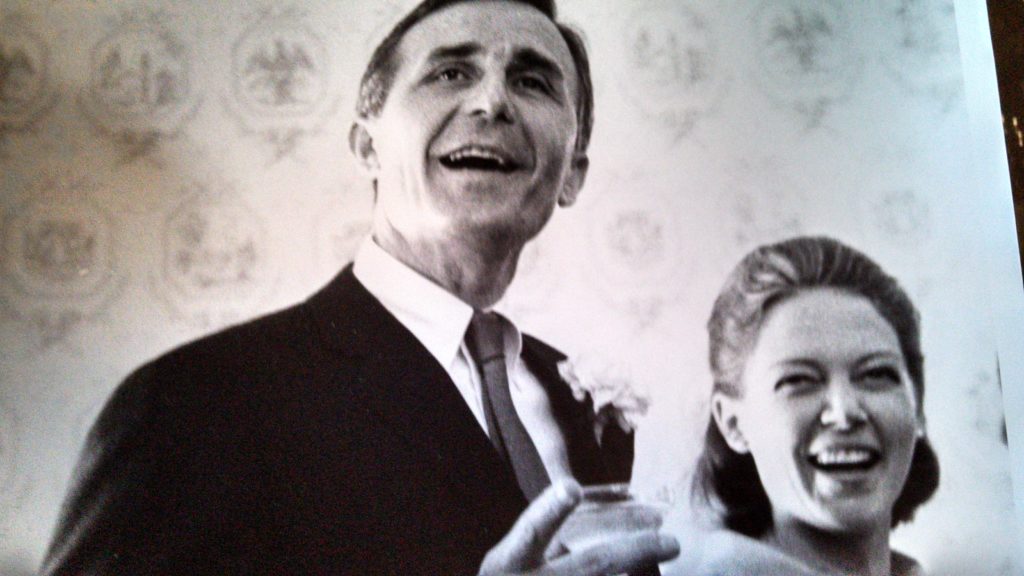

Of course, a few years later my 40-something dad and his 20-something star copywriter had an office affair and she became Carol Murray.

So, erotic love has gone out of fashion in the corporate world, as agape love has come in. Like I said at the top, corporate love is a many-splendored thing.

Try to keep up, Gaga.

Great family story. Thanks for sharing.