My first boss Larry Ragan was suspicious of kinder, gentler management language that seemed to gloss over the essential power relationships between bosses and employees. He’d had a lot of bad jobs in his career, working for bad bosses, and it was hard for him to believe that every new boss, himself included, was suddenly going to “empower” employees, and become their “coach,” and “mentor.”

Rhetorically, he asked, was his first boss Violet, at the Olsen Trucking Company, being a “mentor” when she let him swig out of her bottle of Pepto Bismol after he’d grossed out on Pepsi-Cola one hot August night?

Similarly, I’m skeptical when I read in Fast Company—the magazine that devoted many pages to “the new economy” 25 years ago, until the dot com bubble burst, and we never heard those words again—that these days, employees want two kinds of respect. Even Aretha Franklin didn’t ask for all that!

Danielle LaGree, an assistant professor of strategic communication at Kansas State University who led the study, says past research has found that there are two types of respect that employees experience. There’s “respectful engagement,” which refers to being a good member of the team and doing a good job; and “autonomous respect,” which has to do with feeling respected for who you are beyond your position.

“They can invest in employees’ personal development, in addition to professional development, to help them become better citizens of society,” she says.

“Egads!” Larry would have typed on his old Royal. Or, “Gadzooks!”

I’m not sure how Larry would handle all the talk about the need for leaders to be “vulnerable” all the time. Yes, I am.

I was reading a piece in Entrepreneur from a young man named Zack Eberwein:

As a first time CEO, I’m uncomfortable — a lot. At 26 years old, my experience isn’t yet very broad and if I’m being honest, leading a category-defining organization where the board and executive team average a decade or two older than me, can feel awkward.

And I’m okay with that.

In fact, embracing the discomfort that comes with being a young leader and knowing my perspective is limited has become my secret weapon. …

I make a lot of mistakes. When I do, I like to share my lived experience and the lessons learned openly with my team. Exposing that you’re imperfect may feel like a weakness, particularly when you’re a young leader like me, but getting it wrong can be one of the best ways to humanize yourself and build trust with your employees.

I don’t throw around the term “privilege” for reasons I have written about forcefully and frequently. But if the above claptrap isn’t that, then what is?

There isn’t a whole new way to lead employees, post-pandemic, post-George Floyd.

People still want to know two essential things about their leader—two things that are a little bit in tension with each other:

- Is this person enough like me to understand me and care about me and what I care about?

- Is this person also special enough to lead this institution into the unknowable future?

Yes, showing some vulnerability can help with number one, above. But showing vulnerability isn’t a core leadership competency, and it never will be.

For all but the most exceptionally communicative leaders, the largest difference between the leadership of yesteryear and the leadership of today amounts to style. Modern leaders use more personal language and—often at the heroic urging of their speechwriters—dwell less on statistics and tell more stories. Speak less in bromides and more in specifics. Appear in more spontaneous communication settings—employee town hall meetings, and listening sessions—and rely less on scripts and lecterns. Open collars rather than ties and pop culture rather than de Tocqueville.

An old-school communication style sticks out these days, as it did to me reading a platitudinous quote the other day from the new CEO of Procter & Gamble, that might have been ghostwritten in 1975: “I am honored to serve as P&G’s CEO. My confidence in the future is rooted in my confidence in P&G people. They are committed to lead, motivated to win, and have a strong focus on sustained excellence in everything we do—serving consumers and delivering for shareholders through an integrated strategy that is delivering balanced growth and value creation.”

Modern leaders have got to sound more humanoid than that.

But they’ve got to deliver the same goods they’ve always had to deliver: the common touch, and the simultaneous sense that they know exactly what they are doing. They’re still the boss, and you’re still not, and they have to help you feel there’s a good reason why.

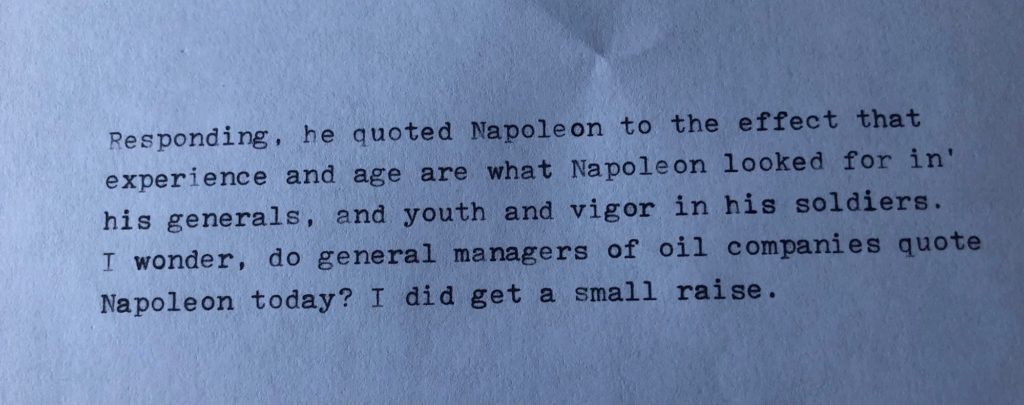

Larry’s 27 years gone. Let’s give him the last word on the changing language of leadership, and the stubborn reality of power: In his memoir, he wrote about the time he asked for a large salary increase from his boss at another early job, at a local Chicago oil company called Cities Service:

Leave a Reply